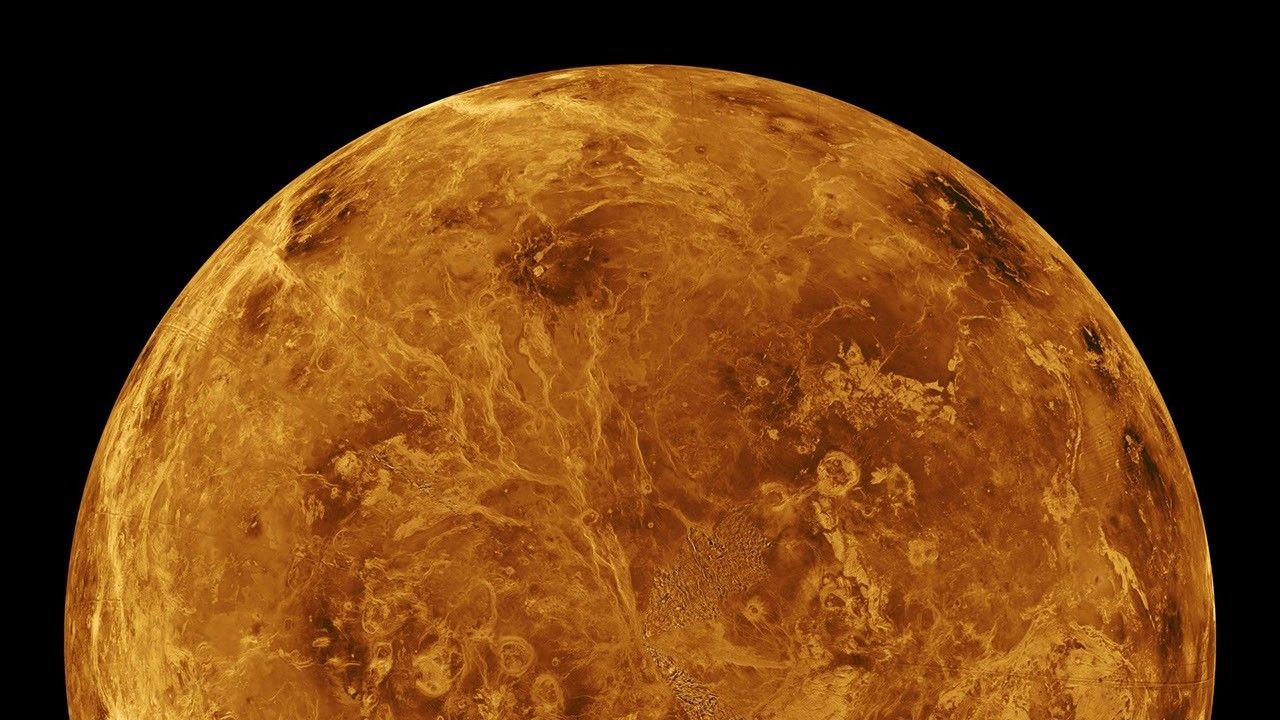

Venus, often written off as a geologically dead world, is far more active beneath its blistering surface than previously thought, according to new research.

Unlike Earth, Venus lacks the geological churn of plate tectonics that regularly recycles and sculpts its surface. For years, scientists assumed that Venus' crust would gradually build up without this process , growing thicker as new rock stacked on top. However, a different kind of planetary engine may be at work beneath this world's surface, one that prevents the crust from thickening indefinitely by causing it to break off or melt once it reaches a certain threshold.

"This breaking off or melting can put water and elements back into the planet's interior and help drive volcanic activity," study co-author Justin Filiberto, the deputy chief of NASA's Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division in Houston, said in a statement. "It resets the playing field for how the geology, crust and atmosphere on Venus work together."

The new study, led by planetary scientist Julia Semprich of The Open University in the U.K., used computer models to simulate how different types of rocks in Venus' crust behave under the planet's extreme heat and pressure.

The findings suggest the planet's crust undergoes a kind of metamorphism; as the crust thickens, the bottom layers become heavier than the mantle below, causing them to peel off and sink downward. The planet's crust likely maxes out at about 40 miles (65 kilometers) thick — and, in many places, it may be much thinner, the study suggests.

"That is surprisingly thin, given conditions on the planet," Filiberto said in the statement. This mechanism, the researchers suggest, could explain why Venus remains geologically active despite lacking plate tectonics.

Recent analyses of archival data from NASA's Magellan mission have also challenged long-held assumptions about Venus's geological dormancy, revealing compelling evidence of volcanic activity as recent as the early 1990s.

"We don't actually know how much volcanic activity is on Venus," Filiberto said in the statement. "We assume there is a lot, and research says there should be, but we'd need more data to know for sure."

That data could arrive in the early 2030s, when NASA's DAVINCI and VERITAS missions — alongside the European Space Agency's EnVision — will study Venus's surface and atmosphere in greater detail. These missions could confirm whether metamorphism and crustal recycling are shaping Venus today, and how they may drive its volcanic and atmospheric changes, according to the statement.

This research is described in a paper published March 25 in the journal Nature Communications.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·