ARTICLE AD BOX

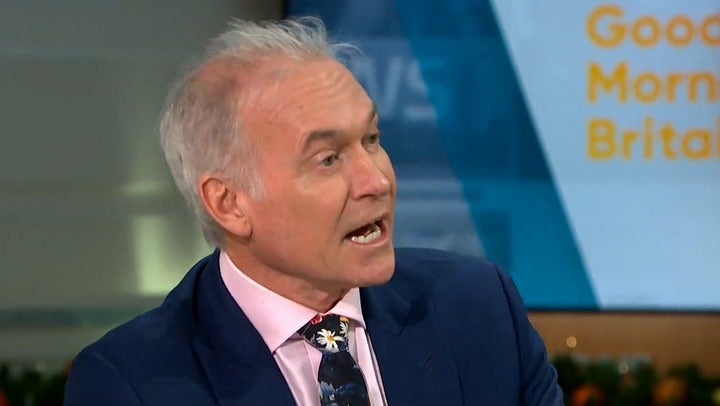

TV doctor Hilary Jones has said he would help a terminally ill patient to end their life if the law was changed, describing the practice as “kind and compassionate”.

The GP, often seen on ITV’s Good Morning Britain and the Lorraine show, said medicine will go “back to the Dark Ages” if proposed legislation being considered at Westminster is voted down.

The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill will return to the House of Commons for debate on Friday, with MPs expected to consider further amendments.

In its current form the Bill, which applies only to England and Wales, would mean terminally ill adults with only six months left to live could apply for assistance to end their lives, with approval needed from two doctors and the expert panel.

Last month, MPs approved a change in the Bill to ensure no medics would be obliged to take part in assisted dying.

Doctors already had an opt-out but the new clause extends that to anyone, including pharmacists and social care workers.

Speaking to the PA news agency, Dr Jones said medics are currently “looking over their shoulders because of the legal repercussions of the law” as it stands.

Encouraging or assisting suicide is currently against the law in England and Wales, with a maximum jail sentence of 14 years.

Asked about the significance if the law does change, Dr Jones said: “It will relieve healthcare professionals who deal with terminal illness.

“There are wonderful people who are caring and compassionate, who just live in fear of their actions being misinterpreted, of being accused of wrongdoing, and because of that fear, people at the end of life are often under treated.

“People are looking over their shoulder because of the medications they’re using or the doses they’re using, it means that patients aren’t getting the best palliative care that they could have.”

Ahead of last month’s Commons debate on the Bill, two royal medical colleges raised concerns over the proposed legislation.

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) said it believes there are “concerning deficiencies”, while the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPsych) said it has “serious concerns” and cannot support the Bill.

But Dr Jones, who has been practising medicine for more than 45 years and spent time working on cancer wards during his career, said he has “always supported it (assisted dying)”.

He added: “I’ve always felt it is the most humane, kind and compassionate thing that relatives and doctors can provide, knowing that that person’s wishes are respected and known, that there is full mental capacity and that they’re surrounded by love.”

Asked if, were the law to change, he would be content to help someone who had chosen assisted dying at the end of their life, he said: “Absolutely, if I know the patient, I know what their wishes are, I see them suffering, and there’s nothing more I can do to help their suffering then, absolutely, I would hold their hand and help them achieve what they want to achieve.”

Some of the Bill’s opponents have urged MPs to focus on improving end-of-life care rather than legislating for assisted dying.

But Dr Jones said his mother, who was a nurse and died “suffering unnecessarily” despite the “best possible palliative care” would be “proud of me speaking on this subject now, in the way I am”.

He told of his respect for people’s “religious beliefs, cultural beliefs and personal feelings” in being opposed to assisted dying but insisted it should be an area of choice.

“The bottom line is that I think it’s the patient’s individual choice. I think we should respect the right of the individual to choose what they want”, he said.

“This is not a mandatory thing. This is not being imposed on anybody.

“And I think people should have the individual right to make a decision about how they end their life if they’ve got a terminal illness where there’s no prospect of cure and they’re suffering and they fear an undignified death.”

Asked about the prospect of the Bill being voted down by MPs, Dr Jones said: “We would be back to square one, back to the Dark Ages, in my opinion, medically, and that would be a shame. I don’t think we would be advancing medicine if the Bill is not passed.”

Our Duty Of Care, a group of healthcare professionals campaigning against a change in the law, said the question must be whether someone is making a “true choice” if they apply for assisted dying.

Dr Gillian Wright, a spokesperson for the group, said: “If someone has not had access to palliative care, psychological support or social care, then are they making a true choice?”

“At a time when the NHS is on its knees, when palliative are social care are struggling and our amazing hospices are having to close beds and cut services because of lack of money, as someone who has cared for people at the end of life, I would urge MPs to vote against this Bill but instead invest in excellent specialist palliative care, social care and psychological support.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·