ARTICLE AD BOX

Turnstile’s Brendan Yates was curled up in bed at his Baltimore home during Charli XCX’s recent Coachella set – oblivious to her announcement that “Brat Summer” was sort of over and “Turnstile Summer” was about to begin. It wouldn’t remain a mystery to him for long; within minutes, millions had seen his band’s name plastered in all caps on a towering screen behind her. “I thought it was a joke,” he smiles, remembering how his phone lit up with messages from friends trying to get his attention. “I was like, ‘What is this AI image?’”

It’s six weeks later, and the 35-year-old frontman is briskly strolling through a leafy park in Los Angeles, his tawny hair bouncing, as he recalls the pop star’s premonition over a video call: “She’s really special and makes music that resonates with a lot of people, so to get that nod was really nice.” It was unexpected for a pop star, even one as preternaturally ahead of the curve as Charli XCX, to offer such a glowing endorsement of a hardcore band, but that’s a limited descriptor for Turnstile, a group who operate with a similarly leftfield vision as her.

While Turnstile emerged from the early 2010s hardcore scene, they always stood out – not just because of Yates’s dynamic singing or their aversion to the black uniform of hardcore, but for their unique musical DNA that connects with a sprawling and diverse audience. Their music is still, on the surface, what the average listener might identify as hardcore – aggressive riffs, breakneck shouts for vocals, excitable breakdowns – yet just as often, it’s none of those things. Turnstile’s existence raises a better question: what is hardcore now, anyway? They’re Demi Lovato and Miguel’s favourite band. Metallica love them; so do Blink-182, who chose them as support acts for their 2023 North American stadium dates. To me, their otherworldly sound is what I imagine would happen if highly trained jazz musicians improvised the rock songs of their teenagehood while a little waved on psychedelics. Across their breakout punk album, 2018’s Time & Space and the three-time Grammy-nominated dream-pop-rock album Glow On (2021), their songs are seething and cathartic, but overflow with joy and an infectious sense of optimism. Life is good, Turnstile seems to say, as long as we maintain our spontaneity.

Their imminent fourth album, Never Enough, is one of the year’s most anticipated releases – but Yates remains immersed in the creative process, largely able to ignore the surrounding buzz. On our video call, he smiles in a blue sweatshirt and wire-rimmed glasses, en route to the edit suite where he’s working on the album’s accompanying film, Turnstile: Never Enough, co-directed with the band’s guitarist Pat McCrory. They’re cutting it fine, the deadline only a few days away.

Yates is serious and considered with everything he says, letting responses meander and peter out if he doesn’t have a good enough answer. Nothing, apparently, is released if it’s not well-conceived, including his own thoughts. “The film is very intentional and abstract in a sense. It’s not a narrative with dialogue; the music is the main character and the visuals are the result of that.” He trails off. “When the album comes out there’s the context. If anyone has the patience or desire to see it in context…”

Making a visual album, he explains, is something he’s always wanted to do, since making music is a visual experience for him. It made sense that this would be the album to attempt it with: though it has 14 songs, it’s made to listen to as one continuous song. Excitingly for Yates, the film is premiering at Tribeca Festival the day before album release, having been accepted off the back of a few clips, rather than the completed film.

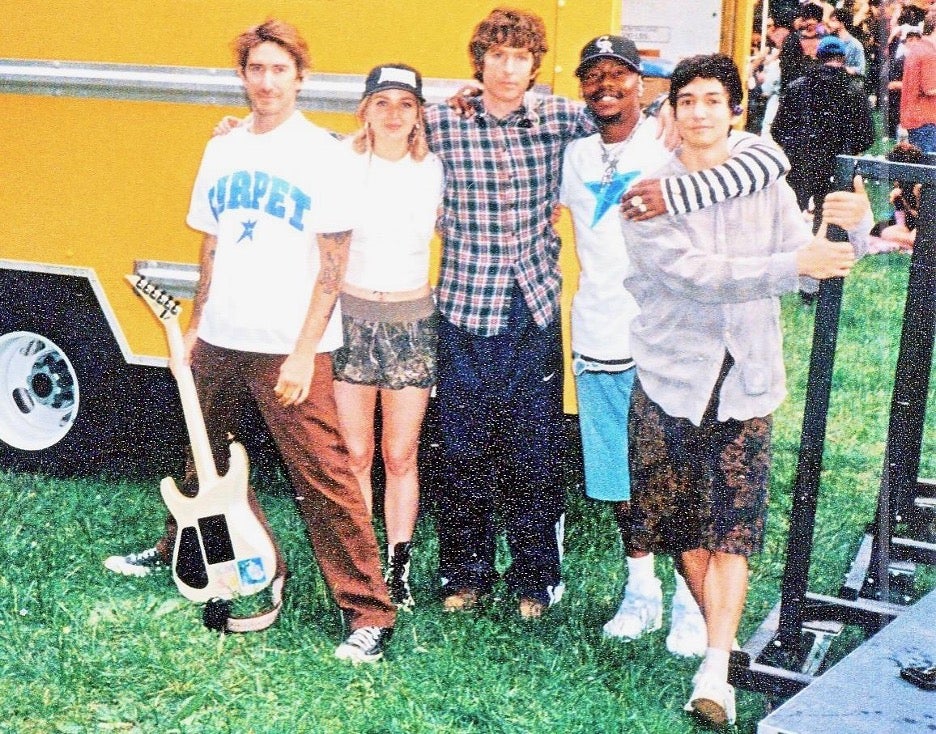

Yates has no training in film, but then he’s not a trained singer either – he started out as a drummer. That’s reflective of the DIY spirit in which Turnstile was formed and still operates: passion and instinct first, experimentation later. Turnstile – whose members now include founding members drummer Daniel Fang and bass and percussionist Franz Lyons, guitarist McCrory and a new addition to the ranks, Meg Mills (Chubby and the Gang, Big Cheese) – began as a conversation within a friend group of: “Alright, let’s do a band where Brendan’s singing”. Lyons, Yates’s best friend, figured out how to play bass from scratch to join them. Yates even taught himself guitar wrong, which means he has to take creative mistakes or measures when writing and playing music. All of them came from a hardcore punk background but that’s an asset rather than a limitation: “With this band, you just learn what you like and what you’re drawn to, and you follow that, and always change.”

The accessibility of hardcore punk shows with their low barrier to entry is something Yates partially credits with fostering this spirit in him and his friends during their teenage years. “You don’t necessarily need to be this amazing musician just to step inside the room, you just need to care about being there and be excited about doing something.”

When Yates grew up in Baltimore – home to a thriving hardcore scene, where he and the original band members still live – he played in every school concert band he could for an opportunity to play. During an aimless time at college, he was asked to go on an extensive tour with the hardcore band Trapped Under Ice, for which he is the drummer. “It’s not that playing in a band seemed like a feasible, realistic option. I had supportive parents. Even with that, the illusion that you have when you’re young is subconsciously still in you: this isn’t as important as these things that you need to do,” he says of his short-lived college experience. Touring the world shifted his perspective. In 2010, he formed Turnstile with his friends to pursue more expansive creative ideas.

Eight years later, with their second album Time & Space, and first on hard rock label Roadrunner Records, they turned every head in rock music by blending indie rock and psychedelic grooves with stadium-filling anthems that were still firmly hardcore. The programmer of Outbreak festival, the UK’s biggest hardcore punk festival, tells me that from this point onwards, Turnstile completely redefined what hardcore was. “They’ve become like a generational band the same way that bands like Fugazi and Bad Brains did,” he says, adding that they’ve been key in making hardcore music far less genre-bound and stylistically regimented compared to when he started Outbreak in 2011. “Almost everyone has their own individual sound now. Before, it was very much like, ‘This is hardcore, and this is how it sounds, and these are the people that come to it.’ It was in one lane. Now, it’s so broad with so much variety, which means other people get interested in the scene.”

Yates is not dismissive of my obvious and now-mundane talk of how the band grew up genre-agnostic. He’s a jazz fan who had a jazz pianist grandfather and an older sister who put him onto the Wu-Tang Clan and Smashing Pumpkins. Other members listen to R&B, dance music, city pop, and classical. “There’s a level of subconscious influence that I feel just exists and is not really smothered; we let it exist and just let it happen,” says Yates of Turnstile’s sound pulling from these places. Members follow their curiosity and nothing else: “We’ve never made a song to fill the quota of a kind of song; songs are a result of what feels good and right to get out.” Perhaps, that’s why people who expect to like their music don’t, Yates suggests, and those who are as curious as its members might find that they click with it.

I saw Turnstile live at an otherwise apathetic music festival in LA a few years ago – where the crowds and other bands seemed largely indifferent. Turnstile electrified the place with their shockingly clear sound. As though an agitated bee’s nest had been dropped onstage, their kinetic energy infiltrated the crowd and had everyone dancing, shocked to be alive. Once Never Enough is released on 6 June, Turnstile Summer will live and breathe in those performances: in the UK, later this month, they play Glastonbury and headline Outbreak. After multiple years of the band playing Outbreak, including for their first-ever UK performance, this year’s bill has been chosen to complement Turnstile themselves. “It probably sounds crazy to base your entire concept off of one artist…” admits their programmer, but that’s how central this band are in the scene they began in.

To record NEVER ENOUGH, the band decamped to The Mansion in Los Angeles, a Laurel Canyon studio compound that birthed some of rock’s biggest hitters, including Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Blood Sugar Sex Magic and Slipknot’s Vol. 3: (The Subliminal Verses) as well as Jay-Z’s hip-hop hit “99 Problems”. When asked what they did in the city around working, Yates almost laughs. “No, we wouldn’t leave the property. We would just stay in the house,” he says, kindly, explaining they had free time in the morning to journal or work out and then they’d record all day until bedtime. Two friends who did break through the band’s seclusive forcefield casually ended up on sparkly mid-tempo single “Seein’ Stars”: Blood Orange musician Dev Hynes, who Turnstile has worked with before, and Paramore’s Hayley Williams. Of Williams, Yates says, “We were just throwing paint at the wall with her decorating our song with her angelic voice; it was really special.”

He prefers not to go into detail on the themes of Never Enough but says lyrics are, as ever, highly specific to him personally. “Vastness and this idea of being a small piece in a larger universe and the fear or peace that can come from that is a theme that makes its way around the album a bit,” he says, as well as learning how to accept love. There’s a third overarching idea: “How maybe intuition is always there, but there are these constant efforts to just fight against your own intuition. I’m trying to bring attention to that.”

No intuitive nudge goes ignored across the 14 tracks of Never Enough, an irrepressible album that picks up exactly where they left off four years ago – only now, they’re pushing further in every direction. It’s heavier, more melodic, more solid yet fluid, and even more carefree in its experimentation. On the frenetic, itchy track “Dull” – built for night-time drives under the influence of revenge or lust – Yates sings, “Deep in the night / I’m waiting for the call.”

It slides seamlessly into the aggressive, power-metal-meets-thrashing-punk of “Sunshower”, which halfway through melts into Eastern flutes and blissful synths for reasons that don’t matter, because it totally works. Then, a drum roll and acidic noise coyly summon the burst of aggression that is “Look Out for Me,” all breakdown riffs and Yates screaming, “Now my heart is hanging by a thread”.

The penultimate track, “Time is Happening,” is an arena rock anthem – cheery enough to pass for a Christmas song, but one that delivers a stark reminder of Turnstile’s core motif: that time is real, fleeting, and meant to be seized. This message hums away inside their sound, which – ironically, and almost aggressively – exists in some otherworldly, atemporal vacuum. “In the right place / At the right time / And still you sink into the floor,” Yates quips on the title track at someone who couldn’t rise to the moment.

Production, nearly solely done by Yates for the first time (with just additional work from Time & Space’s producer Will Yip), is painfully sentient: spitting and breathing and roiling organically to the album’s merit. Like the vast majority of Turnstile’s music, these songs were created in isolation by Yates, before he brought them to the other members to interpret with their own flavour.

That ever-constant instinct he mentioned earlier is something he’s trying to have more faith in, within music, as well as life: “I think I can be really hard on myself, I’m trying to figure out how to be a little easier,” he admits, adding that often he’ll play with an idea for a song, beating himself up about not getting it right, testing different iterations of it, only to return to the original. “I’m trying to get better at trusting intuition and embracing the intangible and not needing to be so hard and critical of myself because I think that can be a never-ending cycle if you do that. Most people who make music might feel the same way; it’s like nothing’s ever finished and even when a mix is done, you spent months and months on it, put it out and [say], ‘I wish I would have turned that hi-hat up.’”

It’s Yates’s band members who avert his spiralling off into second-guessing musical decisions. “Their perspective can be affirming in either direction, and it can even just make you see something different.”

Yates admits that it’s not easy to build such a solid collaborative base from which to freewheel for 15 years. “A dynamic within a band is much different than anything else I’ve experienced in life, in a way that’s just very intense and the most beautiful and complicated and in every way,” he says thoughtfully before signing off at the studio, minutes ticking down toward his deadline. “The fact that the band can exist for this long and everyone still deeply loves each other – it feels like a miracle sometimes.”

Turnstile’s ‘Never Enough’ is released on Roadrunner Records 6 June 2025

English (US) ·

English (US) ·