ARTICLE AD BOX

It’s a scene that has played out in community centres up and down the country. A cluster of people, most of them women, inevitably, are nervously waiting to stand on the scales in front of their peers. Will they have lost or gained a few pounds since their last communal weigh-in? But although set-ups like this were once a defining part of diet culture, soon they may become extinct entirely, an archaic throwback to another era.

This week, Weight Watchers, the company that commercialised the diet group and has reigned over the industry for around six decades, announced that it had filed for bankruptcy, reportedly in an attempt to eliminate $1.15bn (£863m) worth of debt. Under Chapter 11 rules in the United States, the business has the chance to reorganise its liabilities while continuing to operate. The company also recently revealed a 14 per cent drop in subscribers compared to the same time last year; revenues had decreased by almost 10 per cent over the same period. Its fortunes have been on the slide for a couple of years: in 2024, it reported a net loss of $364m.

What’s responsible for this dramatic change in fortunes? Perhaps the most obvious culprit is the seemingly inexorable rise of Ozempic, and other drugs like it, which have transformed the way that we approach weight loss. Semaglutide was originally developed as a diabetes medication, but over the past few years, its ability to help control blood sugar levels and regulate appetite has made it popular as a so-called “skinny jab”. Ozempic has turned the diet industry upside down, and left more traditional brands struggling to keep up.

Weight Watchers started out in Sixties New York. Housewife Jean Nidetch had struggled with her weight for most of her life, testing out diet pills (including prescription amphetamines – it was the Sixties, after all), crash diets and hypnosis in an attempt to lose pounds. But none of these methods worked; as soon as she stopped, she’d end up putting the weight back on. Spurred on by a neighbour who’d asked her when her next baby was due (she wasn’t pregnant), Nidetch headed to the city’s obesity clinic for advice.

Her experiences with the clinic’s weight loss group helped inspire Weight Watchers; its hallmarks were a plan of recommended and prohibited foods, and weekly group weigh-ins, where a lower number on the scales would be rewarded with prizes (and the praise of your peers). In 1968, five years after its launch, the group boasted more than 1 million members around the world. Ten years later, the business would sell for more than $71m (roughly equivalent to around $347m or £260m today).

By the Nineties, the brand name was practically synonymous with a culture that encouraged women (who made up the vast majority of the Weight Watchers customer base) to constantly scrutinise their bodies and find them wanting. You’d see flyers outside community centres and church halls, advertising weekly meetings, and would hear anecdotes of friend groups and family members (typically mums and daughters) signing up together in solidarity.

Head into the aisles of any supermarket and you’d also spot ready meals emblazoned with the Weight Watchers logo, proudly proclaiming the amount of “points” that they contained. This now ubiquitous aspect of the Weight Watchers universe – whereby certain foods would be awarded a certain number of “points” based on their nutritional and calorific content, and members would tot up their daily and weekly allocation – was in fact only introduced around this time.

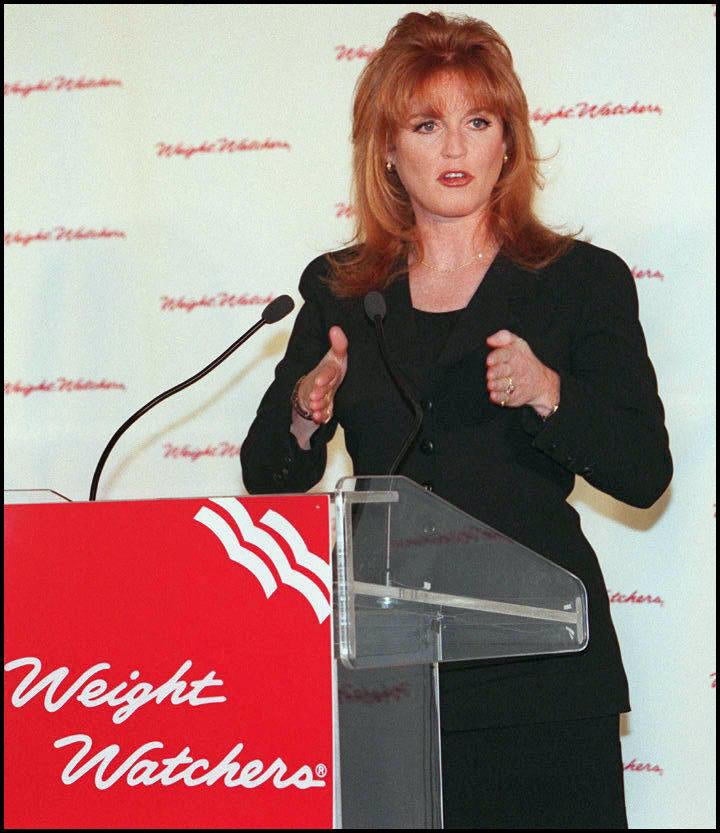

Celebrity ambassadors, including a post-divorce Sarah Ferguson, only seemed to make the brand more omnipresent. In the UK, we also had our own homegrown equivalent, Slimming World, which used a system of “syns” to manage calorie intake. “Syns” were, as you can probably guess, attached to stuff with higher calories – and the counter-intuitive spelling was introduced some time in the Nineties (perhaps the original version was deemed too shamey, because there’s nothing like a superfluous “y” to soften the potential demonisation of certain foods).

Weight Watchers, and all the similar programmes that sprang up in its wake had their own success stories. Many members reported finding a sense of community and accountability in their groups. But the rhetoric of these diet plans was so all-pervasive that, even if you weren’t a paid-up member, it seemed to infiltrate the way you thought about food. Anecdotally, at least, I know of far too many women in their twenties and thirties whose early attitudes to their diet were shaped by the calorie-counting systems they heard about from older relatives, or who still find themselves doing mental maths when comparing food labels in the supermarket aisles.

When programmes like these were everywhere, it was near-impossible not to absorb some of their rhetoric, or to start feeling like you should be scrutinising every morsel that passes through your lips. I’ve never felt more self-conscious of my eating habits than a brief period in the mid-2010s, when a couple of housemates embarked on a Slimming World stint, filling the kitchen with talk of foods that could be enjoyed “unlimited”, and which would be branded as “syns” (side note: I have never, before or since, seen as many low-fat yoghurts as I did whenever I opened the fridge during this time).

By this point, though, Weight Watchers and its ilk were starting to feel out of kilter with a prevailing cultural mood that valued wellness over constant dieting, and body positivity over standing on the scales. But in 2015, Oprah Winfrey helped to revitalise the company’s fortunes when she bought a 10 per cent stake and became its most popular celebrity ambassador yet; three years later, revenue had risen by one-fifth. If it worked for Oprah, people seemed to think, then maybe it’ll work for me.

In 2018, they rebranded as WW, part of an attempt to move away from explicitly aligning the company with, well, weight loss. Instead, their new tag line was “wellness that works”. It’s safe to say, though, that the new name didn’t exactly capture people’s imaginations. The pandemic meant that their in-person weigh-ins were off the cards, so the brand formerly known as Weight Watchers leaned into online plans instead.

Their one-time saviour Winfrey then became something of a canary in the coalmine when, in 2023, she revealed that she’d been using weight loss drugs as a “maintenance tool”. It felt like the first major blow for WW’s more traditional take on dieting, and Winfrey later stepped down from the board. Her departure prompted shares in the company to drop by around 25 per cent.

Where celebrities go, we mere mortals tend to follow. And so has been the case with Ozempic, Mounjaro, Wegovy and other semaglutides prescribed for weight loss. It’s now estimated that around one in eight adults in the United States have used them at one point, and it’s thought that increasing numbers of British people are paying to access the drugs online. These appetite suppressants seem to render a calorie-counting platform like Weight Watchers, well, pointless; you don’t need to stress over adding up your daily points if your semaglutide injection has drastically curtailed the impulse to eat. Weight Watchers did recently acquire a digital health company, with the aim of focusing on remote prescriptions for similar medication, but it felt a bit like too little, too late (although recent stats from the company show that this is one part of the operation that is actually doing OK right now).

Appetite suppressants seem to render a calorie-counting platform like Weight Watchers, well, pointless

As someone with a deep-rooted suspicion of the diet industry in all its many guises, from food-tracking apps to meal-replacement shakes, I thought that I might experience some vague sense of triumph upon learning of Weight Watchers’ floundering. But I’m surprised to find that the victory feels pretty hollow. Why? Because Weight Watchers is the symptom of a problem, not the cause, and it’s not like we’ve managed to stamp out the diet culture that broadly underpins enterprises such as this one.

We’re just as obsessed as we ever were with being thin – we’ve simply found another potential way to achieve it (or, at least, another way to spend lots of money in its pursuit). And Ozempic seems to have ushered in a new era of super-skinniness, where already extremely thin celebrities are shrinking before our eyes, at a speed that previously seemed impossible – all while denying that they’ve ever touched the stuff. It’s all creating a sense of cognitive dissonance that’s arguably just as damaging for our body image; growing up in the size zero epoch of the Nineties and Noughties was bad enough, but I feel slightly sick thinking about the messages that young girls are absorbing now.

The brave new world of weight loss jabs makes the traditional diet group seem almost quaint by comparison – at least, you might think, those programmes fostered some sense of togetherness, rather than having us injecting meds in silo and, in some cases, in secrecy. The decline of Weight Watchers isn’t a sign of a better culture around weight loss and diet – just a more complicated one.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·