ARTICLE AD BOX

A fine mist accompanies the clan as the sun rises and they begin their journey. There are 12 people in total, some of them adults, some children, and others so small that they have to travel on the backs of the women.

This is one of the human groups that frequented the Pyrenean Mountains during the period known as the Last Glacial Maximum, or Ice Age. These Homo sapiens – nomadic hunter-gatherers who populated Western Europe between 11,000 and 35,000 years ago – carry with them a leather rucksack containing objects of value: mostly flint cores and flakes that they will use on the journey as hunting tools, or as ornaments. These are pieces of their homeland.

By mid-morning, the group arrives at their destination for the next few days: the wide Pyrenean valley of Cerdanya, one of the enclaves that, generation after generation, has served as both a refuge and meeting place.

Today this place is known as Montlleó: an open-air Magdalenian archaeological site located high in the Catalan Pyrenees. At around 1,144 metres above sea level, in the Coll de Saig, it is one of the most favourable mountain passes for crossing the Pyrenees. Even during the Ice Age, when glaciers covered much of the landscape, Cerdanya was still passable.

They will spend a few days there, perhaps hunt a horse or a goat and meet neighbouring communities, who have come from both sides of the mountain range and have the same cultural tradition. At these meetings, they share experiences, but also exchange ideas, objects and materials.

Some groups come from the coast, bringing with them an abundance of perforated seashells which adorn their necks and clothing. Others bring small, high-quality flints that they exchange for resources such as deer or reindeer antlers.

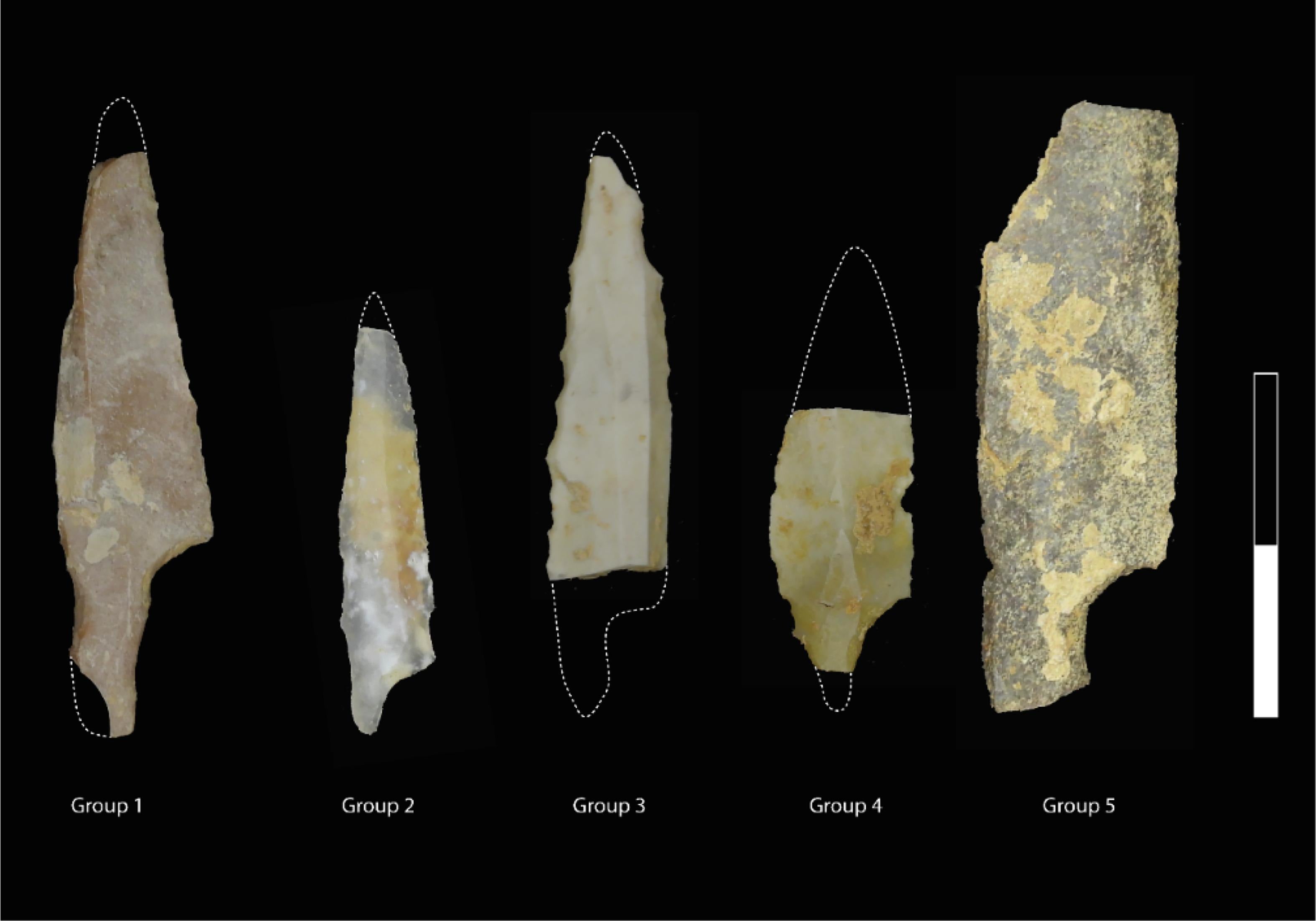

On the first night, they show the projectiles they have made. These objects all have the same purpose: to wound an animal until it dies and becomes food for the group. However, each object is characteristic of its community, made with different varieties of flint and in a particular shape. They are, in a way, a distinctive element of each clan, similar to the tradition shared by the different communities that frequent the Pyrenees.

Mapping prehistoric movements

The archaeological research carried out in recent decades has allowed us to travel back in time in order to complete, little by little, the puzzle that is the study of prehistory.

Archaeological work in the Pyrenees has shown that human populations adapted to changes in the mountain environment and settled in areas that had initially been considered permafrost: permanently frozen ground during the Last Glacial Maximum.

To find out how and where these groups moved in the Pyrenees, we can study the valuable tools and ornaments that they carried with them from their place of origin. The lithic industry discovered at Montlleó is made up of more than 25,000 pieces, of which more than 2,000 are finished flint tools and cores (masses of homogeneous rock that are carved to extract flakes for later use). We have a good number of objects to trace.

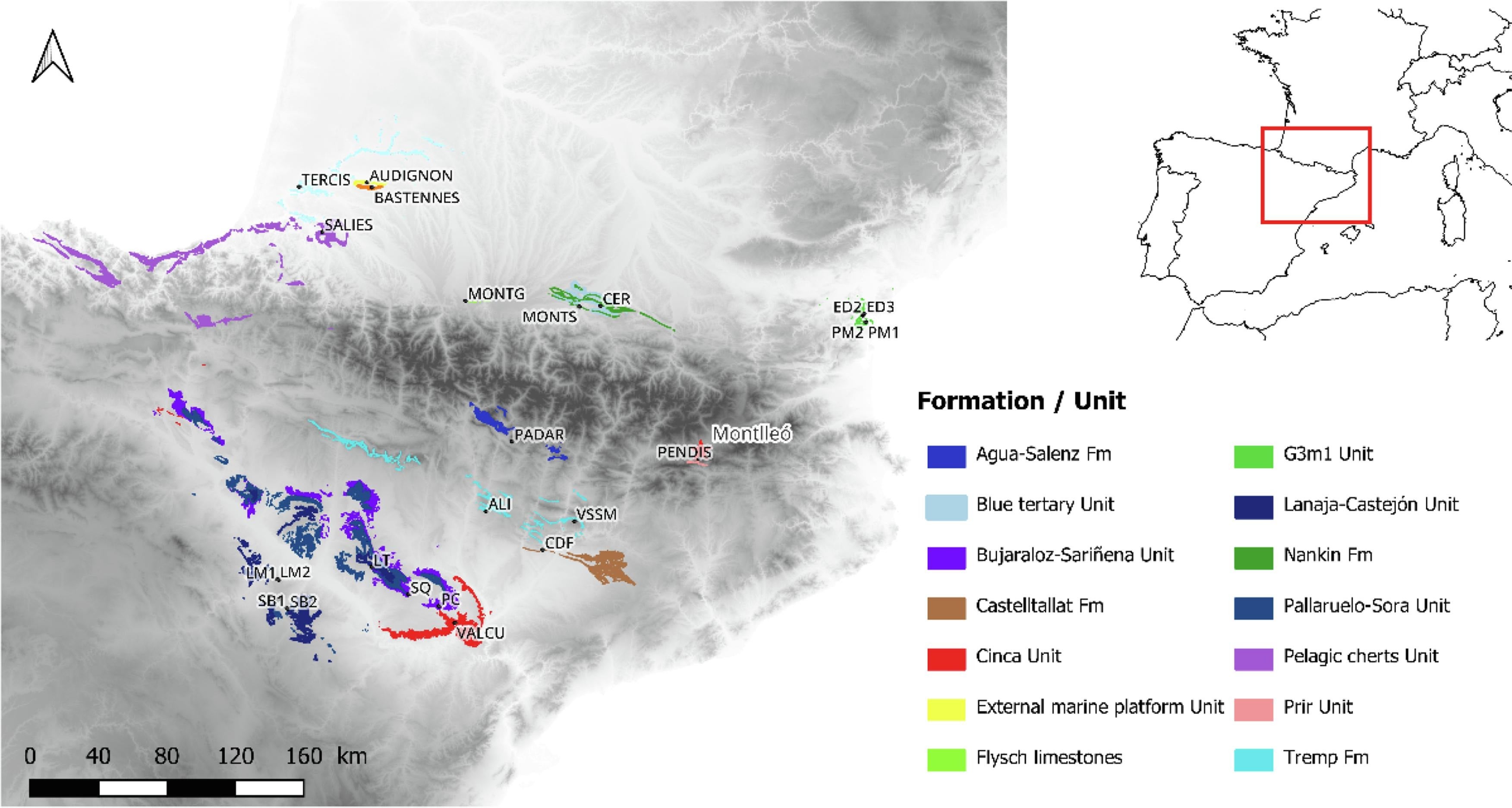

Our research project – named SPEGEOCHERT and funded by the European Research Council (ERC) – traces the routes followed by human groups to cross the Pyrenees. Today we know that the mountains were not a barrier, but rather a passage frequented by the Homo sapiens of the Upper Palaeolithic.

Among the project’s many surprises, three specimens of possible flint from Chalosse have been tentatively identified. They are from the south-west of present-day France and represent, for the time being, the most distant source.

Favourite flints

In order to map out these potential routes, we relied on a very abundant resource in the archaeological record: tools made of flint, one of the most widely used rocks in prehistoric times.

Flint’s characteristics are specific to the place and time of its formation in the Earth’s geology. This allows us to know, after detailed study, the origin of the pieces we find in the archaeological record.

Our team is working to locate and recover samples of geological formations containing flints similar to those found in prehistoric sites. In our research, we are seeing that not all flints have the same territorial extension. In other words, it seems that there were “favourite” flints that circulated more than others.

For our research, we selected these preferred types of flint as tracers or markers. By observing their distribution radius, we were able to track the mobility of the groups that carried them. This included small cores prepared for carving, some crude tools such as blades and flakes, and also finished tools which were ready to be used.

We analysed, at various scales, the archaeological flints recovered from more than 20 sites located on both sides of the Pyrenees mountain range, together with reference samples recovered from other geological formations.

Geochemical analysis then allowed us to establish a match between the archaeological piece and the source area.

Lastly, we applied geographic information systems, which take into account different variables such as topography and even the prevailing climatic conditions. With all this, we suggest the routes that these populations may have followed to acquire flint, which, in short, allows us to know where they moved and what relationship they had with the mountain areas.

It is now recognised that at least two main natural corridors for crossing the Pyrenees were frequented by prehistoric human groups: the “Basque Crossroads” in the west and the Cerdanya valley in the east. What this tells us is that human presence in high-altitude open areas during the Ice Age was not just a possibility, but a reality.

Marta Sánchez de la Torre is a Profesora agregada de Prehistoria at Universitat de Barcelona.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·