ARTICLE AD BOX

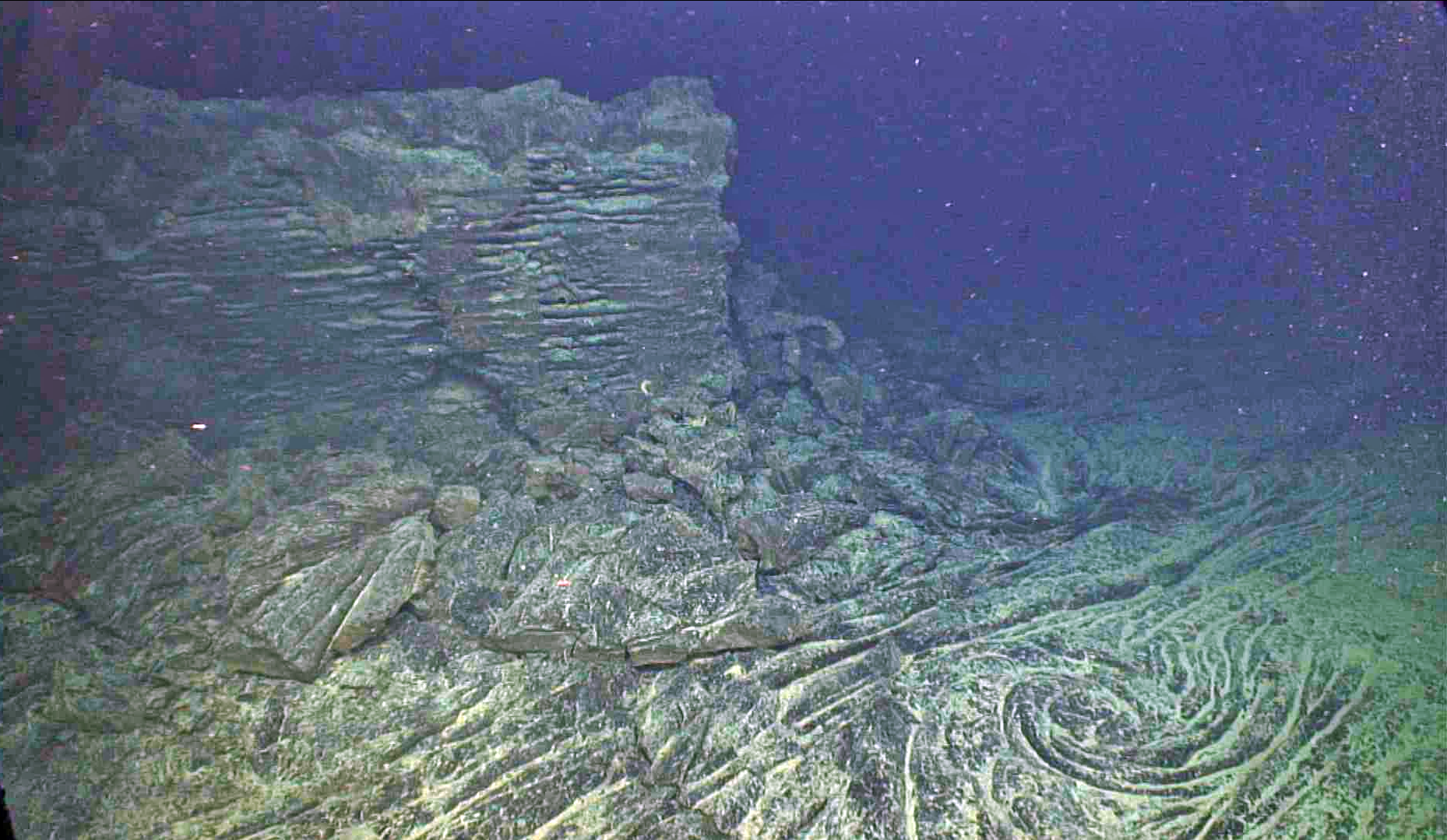

The Axial Seamount – located hundreds of miles off the coast of Oregon and nearly 5,000 feet below the Pacific Ocean’s waves – erupted in April 2015, spewing a mile’s worth of lava onto the sea floor.

And now, the Pacific Northwest’s most active underwater volcano is getting ready to erupt again - although no one is exactly sure when or what will happen.

“Over time, the volcano inflates due to the build up of magma beneath the surface,” William Wilcock, a marine geophysicist and professor at the University of Washington, said in a statement.

“Some researchers have hypothesized that the amount of inflation can predict when the volcano will erupt, and if they’re correct it’s very exciting for us, because it has already inflated to the level that it reached before the last three eruptions. That means it could really erupt any day now, if the hypothesis is correct,” he added.

There’s a lot that remains unknown about submarine volcanoes and how they erupt, however, largely because of where they occur: obscured from the view of scientists.

So, how do we know an eruption may be imminent other than inflation? Seismic activity gives scientists a clue. Right now there are 200 to 300 earthquakes a day around the Seamount. Some days, due to tidal activity, there have been 1,000. Right before the eruption, Kelley said they would expect to see as many as 2,000.

“Axial is under a state of critical stress now,” noted Maya Tolstoy, a marine geophysicist and the Maggie Walker Dean of the University of Washington College of the Environment. “At high tide the weight of the ocean presses down on the crust, and when that weight is ever so slightly decreased at low tide, the number of earthquakes increases.”

“What will be really interesting to see is whether those factors also affect the likelihood of an eruption by putting additional stress on the magma chambers,” Tolstoy added.

Underwater volcanoes can create unique habitats for marine life, often acting to deflect food-carrying currents upward, attracting fish and other species. Hydrothermal vents on the seafloor where seawater is heated by magma and ejected are an “oasis of life,” and gases the volcanoes emit can help microbes in the deep sea survive. But, they can also lead to ocean acidification and harm marine life.

If the volcano does erupt soon, Pacific Ocean dwellers can expect a startling sound. While whales attuned to low-frequency sounds are unlikely to be harmed by the loud implosion, it will be a different outcome for the creatures that live on Axial Seamount’s hydrothermal vents.

“In 2011, we saw one of the venting areas become completely covered in lava flows,” Kelley said. “It wiped everything out. But what’s fascinating is that when we came back three months later, there were animals and bacteria colonizing the area again. They’re surprisingly resilient ecosystems.”

In any volcanic eruption, magma rises from the depths of the Earth to the surface. The magma contains dissolved gases that form bubbles as the pressure on it is released during its ascent, according to the Smithsonian. An explosive eruption occurs when the gases are released.

Underwater, however, that magma faces the pressure of the ocean. When magma comes in contact with water, the temperature change is so dramatic that it solidifies in a process called quenching.

The Axial Seamount is formed by a hotspot, which is an area in the Earth’s mantle where plumes of molten material rise into the planet’s crust. As that crust moves over the mantle, the hotspot stays in place. That results in the formation of long chains of volcanoes over time.

“Three-quarters of all of the volcanic activity on Earth takes place at mid-ocean spreading centers,” Deborah Kelley, another professor at the university, explained. “But people have never directly witnessed an eruption along this mountain chain, so we still have a lot of unanswered questions.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·