ARTICLE AD BOX

Peter Sullivan has had his conviction for the murder of Diane Sindall quashed. He is not the Beast of Birkenhead. He is an innocent man who got ensnared in a malfunctioning system that then took 38 years to admit its mistake.

He was wrongly convicted in 1987 for the brutal attack on the part-time pub worker. The 21-year-old was beaten to death and sexually assaulted as she walked home after a shift in Bebington, Merseyside.

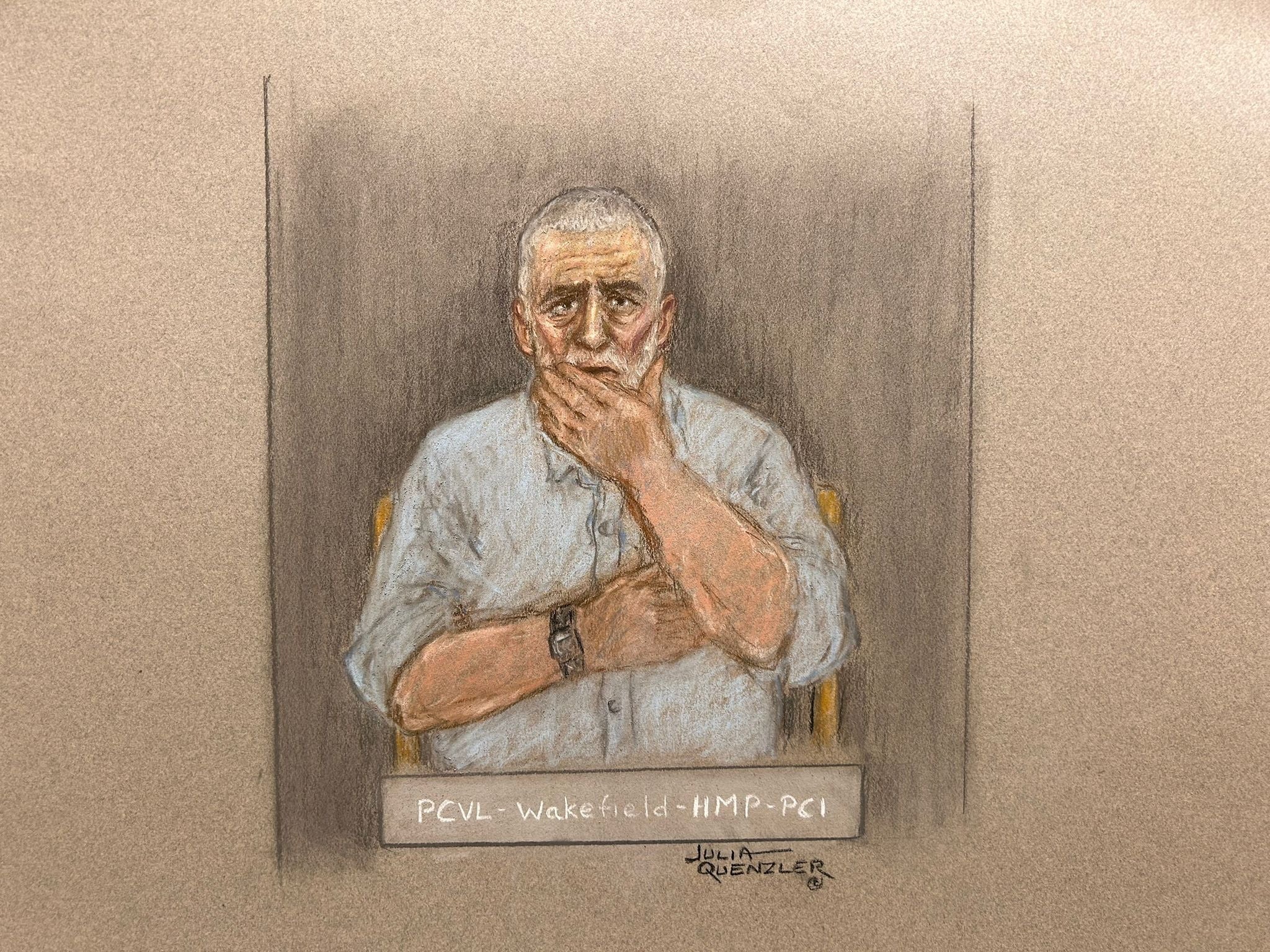

Sullivan is now 68 and has lost the best years of his life. Remarkably, in a statement read by his lawyer after his conviction was overturned, he said he was “not angry, not bitter”. He said he had experienced horrors but would not dwell on them: “I’ve got to make the most of what is left of the existence I am granted in this world.”

Given he’s the victim of the longest miscarriage of justice experienced by a living inmate in the UK, no one would begrudge Sullivan that.

But it would be a mistake to see his case as a bizarre one-off. In March, I wrote in detail about how the English criminal justice system continually betrays victims of injustice – from cases like the Birmingham six and the Guildford four to the hundreds of victims of the Post Office scandal.

There are also immediate parallels to be made with two other miscarriage of justice cases – Victor Nealon and Andrew Malkinson.

The Sullivan, Malkinson, Nealon cases were all exposed as miscarriages of justice thanks to new DNA evidence, but only after a reluctant and incurious appeal system was dragged kicking and screaming into agreeing to new forensic testing.

Malkinson was wrongly convicted of rape and spent 17 years in prison. The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) twice rejected his submissions that he was innocent, and he was only cleared when his own lawyers tracked down DNA evidence that proved his innocence.

Nealon who was wrongfully convicted of attempted rape spent an additional ten years in prison because the CCRC refused to carry out DNA tests that would have proved his innocence. He applied to the CCRC twice but was rejected both times.

In the Sullivan case, the CCRC feels it deserves credit for ordering the retesting that led to his exoneration, and it does. But it’s worth noting that he applied to the CCRC in 2021 and it took until now for him to be freed.

No compensation

Justice delayed is justice denied and all three men spent unnecessary years of their lives behind bars thanks to a sluggish and often inept appeals system.

It took decades, but Sullivan is now a free man. He leaves prison with £89 in his pocket, and that’s it. There will be no automatic compensation, no system that eases him back into ordinary life.

When Victor Nealon was released after 17 years in prison, he would have been homeless if it were not for the kindness of a journalist who allowed him to sleep on his couch. Nealon has never received compensation. After multiple rejections, he and Sam Hallam, another miscarriage of justice victim who was accused of murder, took their claims for compensation all the way to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). They lost.

The judges at the ECHR concluded that it was virtually impossible for victims of miscarriage of justice to receive compensation in the UK, noting that 93 per cent of people who applied for compensation were rejected. The two men have never seen a penny of compensation.

But it appears that Malkinson may be one of the lucky 7 per cent who do. It has been reported that the Ministry of Justice is to pay him “a significant sum” and no one in their right mind would object to Malkinson receiving compensation. He is an innocent man who spent 17 wasted years in prison.

Hallam, Nealon and so many more are also innocent but have been refused compensation. Why?

It is difficult to come to any other conclusion than Malkinson is being compensated because of the media coverage his case attracted. Malkinson is a very impressive person – erudite, thoughtful and reasonable – someone capable of guest editing the Today programme. His case, along with his criticisms, threw the CCRC into crisis and led to the resignation of its chair. But not everyone can be Andrew Malkinson, and they shouldn’t have to be.

Sullivan is a very different person. “He’s a very quiet, private man,” his lawyer told the BBC. He has so far shunned the media and it’s clear that he will not have the same high profile as Malkinson. His story will fade as the news agenda moves on and there will be a danger that the lessons from this case will be ignored or forgotten.

For example, Sullivan’s case is a reminder that there are still people in prison who were jailed based on false confessions, and these cases should be reviewed urgently.

And the project announced by the CCRC to identify cases where new forensic testing could provide fresh evidence needs to happen urgently. As Chris Henley KC, the lawyer who led a review into the CCRC’s handling of the Malkinson case, said, more miscarriages of justice cases are “inevitable” and so it is better to identify them as quickly as possible. No need for more innocent people to languish unnecessarily in prison.

Ultimately, the main lesson for the criminal justice system to learn is humility. If a plane crashes, accident investigators will painstakingly piece the wreckage back together to identify what went wrong. If there is an infectious outbreak, medical experts will urgently seek out the source. They do this so that they can find out what went wrong and avoid future tragedies.

But somehow the criminal justice system appears to feel it is above this approach, despite the fact that Peter Sullivan was failed by the police, by the legal system, courts and the Court of Appeal. As Henley said: “I think that there is a fundamental problem in relation to our appeal system generally, that it just won’t face up to the fact that mistakes can be made. It stubbornly wants to stick to the original flawed conviction.”

But first and foremost, Peter Sullivan must receive the compensation he deserves. He was wronged and the state should swiftly and fairly do what it can to make that right.

Brian Thornton is a Senior Lecturer in Journalism at the University of Winchester.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·