ARTICLE AD BOX

Whenever a storm is about to hit Los Angeles, Mike Hadreas is ready with torches, batteries, and bags packed for what he is convinced will be an inevitable evacuation. “I’m not playing around,” the artist better known as Perfume Genius says with a laugh. “We’ll [end up staying] at home all day, and the next day we’ll hear our friends went to the movies, hung out…” This tendency to fear the worst provides the theme for his self-flagellating new single “It’s a Mirror”, the first from his seventh album, Glory. You hear it in the lopsided, angry guitars, and in the way Hadreas sings “It’s a chorus reaching for us/ Swarming locusts wherever you go”.

As Perfume Genius, Hadreas has carved out a space over the last 15 years in which he is able to thrive as one of America’s most avant-garde pop stars – and one of its most critically acclaimed. His fanbase, with good reason, tends to be obsessive, while his flair for melding elegiac, emotionally acute songwriting with musical pomp has led to two Grammy nominations, for the 2017 album No Shape and for his 2022 collaboration with Yeah Yeah Yeahs, “Spitting Off the Edge of the World”. For him, music has always been the purest form of self-expression.

But it’s also always been a coping mechanism. The only out gay student at his high school in Seattle, he was bullied and beaten up by football players and, at the age of 21, left needing hospital treatment after he was viciously attacked by a group of men. He moved to New York, working as a doorman in the East Village and finding a queer community for the first time. Returning to Seattle, he began making music and uploading it to MySpace, taking his name from the 2006 film Perfume: Story of a Murderer, about a genius perfumer who will stop at nothing to create the perfect scent. His first two albums, 2010’s Learning and 2012’s Put Your Back N 2 It, documented sexual abuse, self-loathing and addiction with startling lyrical candour: “He let me smoke weed in his truck/ If I could convince him I loved him enough,” he sings on “Mr Peterson”, about a teacher he grew close to when he was 14.

“I remember when ‘Queen’ [his 2014 single, which he has described as being inspired by ‘gay panic’] first came out, journalists asked me why I was making such a defiant song in a time where things politically seemed to be ‘better’ for queer people,” he says. “The flipside happened around No Shape – I was asked why some of the songs were less pointedly political when Trump was first in office. Sometimes I consciously write more defiantly, but I think all of the songs in their own way are defiant just by leaving my queerness intact in whatever form it is taking.”

More recent compositions have become more accepting. The big exuberant rock album No Shape sounded how he wanted to be, “liberated and free”. The dazzling follow-up, Set My Heart On Fire Immediately, meanwhile, was a baroque-pop opus, all quivering cellos and gossamer vocals one minute, eerie synths and lonely echoes the next.

Yet given the polarised times in which we live, Hadreas is still keen to use his platform where he can. “Voicing your support for the safety and right for trans people to exist, even for the people of Palestine to be free, is important,” he says. “I’ve read and heard so many stories of people losing their jobs, their platforms, their safety just for the simple act of speaking up. There are trans members of my band and we are scared of passport issues, visas. It’s heartbreaking and scary. America was built on racism and violence and fear. It has been woven in since the beginning. Right now is a very clear and public demonstration of it. I will keep singing and trying to be there and do whatever I can for my queer and trans friends and family forever."

We’re speaking over video call; Hadreas, 43, is at home in LA, his slight figure poised on a chair in front of the camera. A lamp overhead illuminates his bright blue eyes, sharp cheekbones and Cupid’s bow mouth, framed beneath a blaze of strawberry-blond hair. His thoughts emerge out of protracted silences; when he laughs, it’s a bright and sudden burst. That anxiety he speaks of can be traced back to childhood: when he was a teenager, walking to the mailbox would have to be followed by a nap in a darkened room. He’s still prone to feeling very fragile and overwhelmed.

“Writing and performing… I’m willing to do all of that, even if it makes me uncomfortable or anxious,” he says. “But in my daily life, I’m very avoidant and unwilling to do what I understand, intellectually, will get me out of whatever loop I’m in.” His anxiety extends to the pressure to respond publicly on certain issues. “I don’t know how to properly share my thoughts around things question by question because it’s all so immense and terrifying – it always has been, but particularly right now. It’s hard to choose your words carefully because it is so charged and physically triggering too.”

In my daily life, I’m very avoidant and unwilling to do what I understand, intellectually, will get me out of whatever loop I’m in

He’s figuring it out, slowly. “I said no to a few things [for this album cycle] when I’d usually just do everything. I like having it set out for me – even at home, Alan is the one who sets up all our social media stuff.” Alan Wyffels is his partner of 16 years and a classically trained musician. They met in 2010 at an AA meeting, when Hadreas was in his twenties and wrestling with drug and alcohol addiction. He’s been sober – and in love – ever since. Wyffels’ presence across this record is palpable: we hear him playing the sombre-sounding piano on “Dion” and the steady, supportive chords of “Me & Angel”, a hushed, devotional hymn.

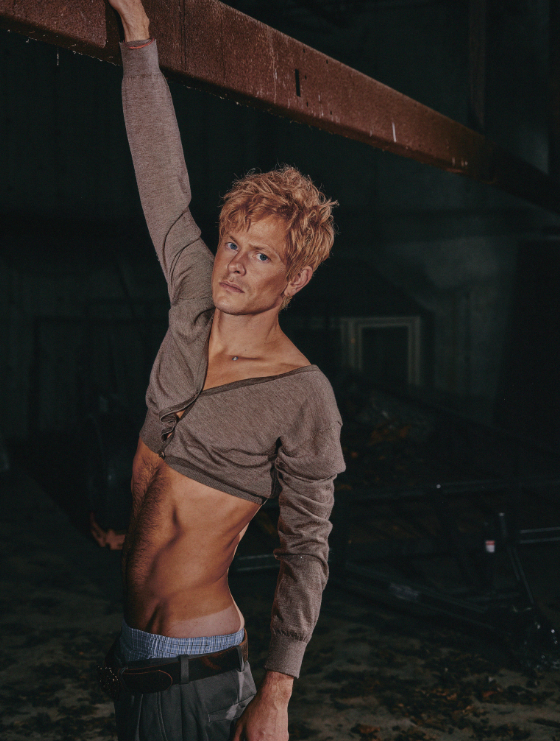

That’s not to say that everything in his life is suddenly easy. Hadreas was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease when he was 12, and his relationship with the body, especially his own, has long provided material for his songwriting. “I wear my body like a rotted peach/ You can have it if you handle the stink,” he sang on 2014’s “My Body”. He tells me he’s spoken with his therapist about how he tells himself that he needs to look a certain way before each album is released in order for it to be successful. “My therapist was like, ‘Well, what if you just showed up the way that you are?’” he recalls. He certainly shows up for Glory’s artwork, appearing in fantastic contorted positions – a handstand on a bed; on his back, legs akimbo on a kitchen floor that also provides the setting for his “No Front Teeth” video.

That video opens with a shot of Hadreas lying prone on an ice-skating rink, surrounded by strangers looking down at him. “Damn, he looks skinny,” one person observes, and you’re not sure whether it’s out of concern or admiration. “I don’t know,” another man says. “He looks kind of sick.” It could be a deft comment on the resurgent trend of thinness in celebrity circles as tabloids and fans obsess over who’s on Ozempic, who’s had cheek fillers, who has an addiction problem. To Hadreas, though, it’s more in keeping with the “you can’t win” battle he has with his own image.

“I think the longer I’m alive, the more I realise I have no handle on how I look,” he muses. “I’ll show Alan pictures of me that I think are flattering because certain things are blurred or not shown there. But that’s not an accurate picture of what makes me attractive, if I am.”

His original styling ideas for the artwork and videos were more “age-appropriate”, he says, until his photographer and director, Cody Critcheloe, suggested that he wear his “jeans really low and have my pubes showing”. He acquiesced, wanting to do things that felt risky. When he was younger, he tried to act more stereotypically masculine as a means of protecting himself from bullies. Now, he subverts it – those all-American jeans slung low over his hips, paired with heeled leather boots and a cropped shirt that exposes his midriff.

He points to the disparity between his own image and Alan’s: “He is very traditionally masculine, he has a very clear currency as an older masculine guy. Like, he’ll put on flannel and he’s a hot daddy. But people perceive me as more feminine, so, if I am going to obsess over my currency, what would that be? If you’re older and feminine and gay, you can be wise, you can be funny, charismatic… but there are fewer examples of it being desirable.”

He’s getting better at self-acceptance. He really likes the pictures of himself on Glory. “I was surprised by them, I was like, ‘I look good!’” he says, with another gleeful burst of laughter. “But it looks like me and it feels like me.” That, in essence, is how he feels about Glory. “It’s more about sharing where I’m at,” he says, “and letting it be.”

‘Glory’ is out now. Perfume Genius is on tour in the US, then in Europe and the UK later this year

English (US) ·

English (US) ·