ARTICLE AD BOX

Russia has signed nuclear energy partnerships with at least 20 countries in Africa, according to new analysis from The Independent, as it seeks to establish itself as the frontrunner in such deals across the continent.

This deals have been funnelled through the state-owned nuclear company Rosatom. The most recent was announced last month with Burkino Faso, which has finalised a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for Rosatom to build a nuclear plant. Other deals include a June 2024 agreement with Guinea to develop floating nuclear power plants and a partnership with Congo to develop nuclear energy and hydroelectric power signed the next month. Since 2014, Russia has also agreed deals with Algeria, Ethiopia, Kenya, South Africa, Tunisia and a number of others.

Other countries pursuing nuclear partnerships with Russia include Niger, a close ally of Russia since the country’s military coup in 2023, which announced last year it is actively seeking Russian investment in its vast uranium deposits. Meanwhile, it was reported last month that Namibia has also held nuclear cooperation talks with Russia.

Of the major countries that supply nuclear technology to Africa – which include the US, China, South Korea, Canada, and France – Russia has established itself as the clear leader. Rosatom boasts a track record of completed projects around the world that other countries are unable to match, and also offers extremely favourable contracts and repayment terms.

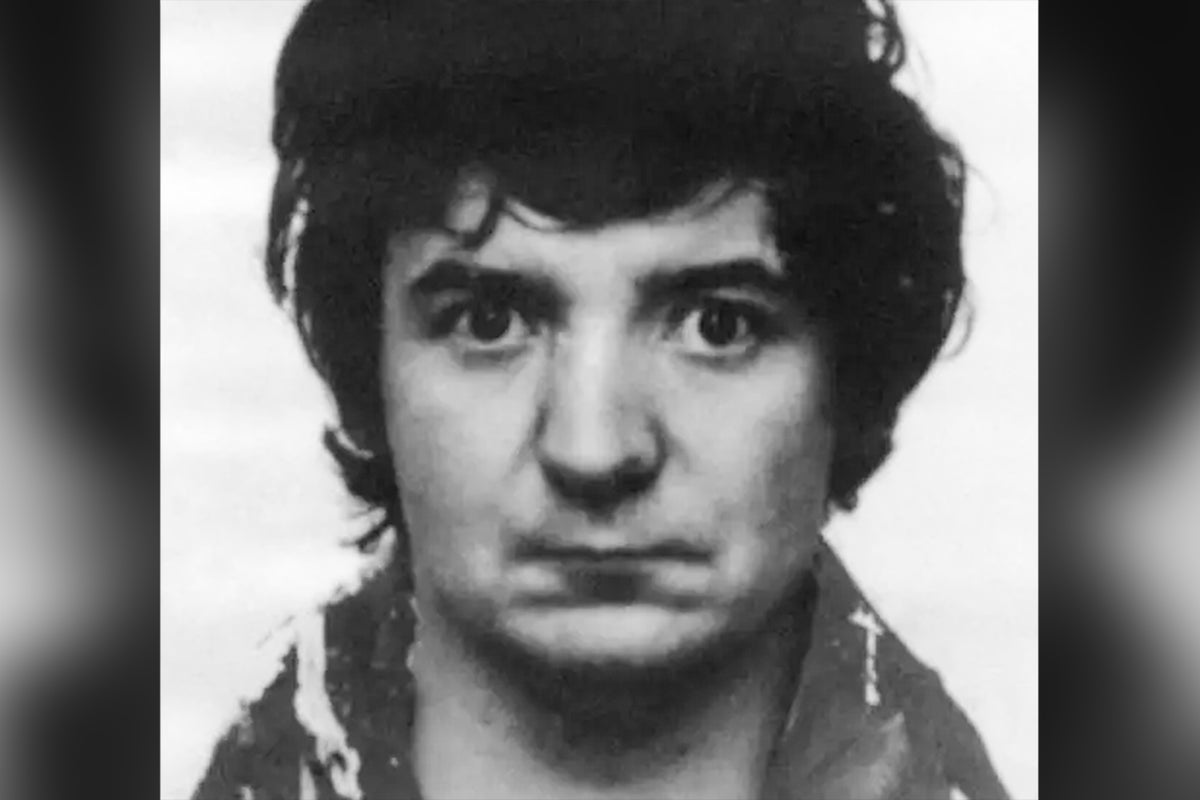

“These agreements are geopolitically significant because nuclear projects are large-scale, long-term commitments that can tie a country to Russia for decades. For Moscow, this is not just about business — it’s also a tool of political influence,” explains Dmitry Gorchakov, a nuclear expert who left Russia to work for the Bellona Foundation environmental NGO in Vilnius, Lithuania after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

“In the context of Russia’s confrontation with the West, showing that it still has international partners is politically important, which is why it is willing to promise a lot to countries that are open to working with it.”

As Russia pushes to grow its sphere of influence through energy infrastructure, the West is moving in the opposite direction, with the US pulling funding for energy projects across Africa thanks to Donald Trump’s international aid cuts. Major US programmes to be terminated include Power Africa, which was established by Barack Obama in 2013 to support economic growth and development by increasing access to reliable, affordable, and sustainable power in Africa.

The past twelve years saw Power Africa deploy some $1.2 billion (£900 million), which in turn catalysed a further $29bn from other funding sources, to develop more than 150 power projects in 42 countries in Africa, and bring electricity to more than 200 million people. Power Africa also supported US companies in $26.4bn worth of deals, according to analysis from the Center for Global Development think tank. The projects supported were a mixture of renewable and gas-fired power projects.

The US has also withdrawn from the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETP), a multi-billion-dollar initiative launched in 2021 to help emerging economies move away from coal and other non-renewable energy sources, with South Africa losing the promise of tens of millions of dollars in grants and another $1 billion in potential commercial investments.

“Without such programmes, it will be even harder for the US not just to compete [in Africa] but even to gain a foothold there,” Mr Gorchakov said. “That’s why they have to put in a lot of effort — and without government-backed support programs, entering these markets will be nearly impossible.”

A crown jewel

The crown jewel in Russia’s nuclear partnerships with Africa is the $28.75 billion (£21.38 billion) El Dabaa Nuclear Power Plant in Egypt, which will become the continent’s second nuclear power plant, arriving some 40 years after South Africa’s ageing Koeberg Nuclear Power Station.

El Dabaa broke ground in 2020, and is set to begin supplying power from 2026. At 4.8 Gigawatts (GW), it will produce enough electricity to power the equivalent of a major US city, and it has been financed 85 per cent by Russia, with highly favourable repayment terms.

Bellona’s Dmitry Gorchakov suggestes that there are several reasons why the prospect of a Russia-backed nuclear plant is so compelling for African countries.

For starters, the deals are backed by the Russian state, which assumes much of the upfront financial and operational responsibility, and offers decades-long repayment timelines at extremely favourable rates. Such deals help make nuclear plants affordable – though they tie the recipient closely to Russia’s nuclear fuel and service supply chains, says Gorchakov.

Western nuclear companies, such as France’s EDF, operate on a commercial basis and cannot provide the same level of state-backed financing, risk-sharing, or diplomatic support that Rosatom offers.

Western nuclear companies have also struggled to demonstrate that they can deliver projects on time and within budget. The expected cost of EDF’s Hinkley Point plant in Somerset has ballooned from £18bn to £35bn, for example, while a project to install two US AP1000 reactors at the Summer Nuclear Station in South Carolina was abandoned in 2017, with bill-payers footing a $9bn after years of delays and cost overruns.

“Political and regulatory constraints also tend to make Western nuclear exports slower, more bureaucratic, and harder to coordinate,” adds Gorchakov.

“Moreover, Western suppliers rarely offer the kind of integrated, full-cycle package that Rosatom provides — including reactor technology, fuel supply, training, waste management, and long-term service — all under a single institutional umbrella.”

China is more likely to offer a full package of support with its nuclear investments – but similar to the West, the country lacks a large portfolio of completed overseas nuclear projects, with only one completed plant in Pakistan.

“In contrast, Rosatom has a much larger active portfolio of ongoing and completed international projects, which allows it to present itself as a more reliable and proven partner in the eyes of many potential customers,” says Gorchakov.

Indeed, according to data from lobby group the World Nuclear Association, which has been analysed by The Independent, Rosatom is responsible for 26 major nuclear power units currently under construction in seven countries around the world: Russia, Egypt, Turkey, India, China, Bangladesh, and Iran.

The four reactors under construction in Egypt are all based on tried-and-tested Rosatom design, adds Jonathan Cobb from the World Nuclear Association. “There are still some first-time challenges in construction, but they can essentially take a cookie-cutter approach based on previous projects they have done,” he told The Independent.

Aggressive energy

For many countries in Africa - a continent where 600 million people continue to still lack reliable access to electricity - a new nuclear plant represents the possibility of large quantities of low carbon, reliable electricity: things that neither variable renewables like solar and wind, nor polluting coal-fired or gas-fired power stations, can match.

Robert Sogbadji, coordinator of Ghana’s national nuclear power programme, envisages nuclear power as complementary to the country’s plans to build more renewables. It is currently hoped that the country’s first large-scale nuclear plant can be completed by the mid-2030s.

“If we want base-load energy to support our renewable ambitions, then we have to continue aggressively on our nuclear power programme,” he told The Independent.

Ghana has chosen the US to build small modular reactors (SMRs) - a modern, smaller nuclear reactor that can be housed in smaller plants – but is in the process of choosing who will provide the technology for its first large-scale plant, Sogbadji said. Russia is in that mix.

Nuclear power remains controversial, with concerns about long-term nuclear waste storage, while relying on large power plants, rather than renewable energy sources spread across the country, potentially makes the power grid more vulnerable to risks like cyber attacks or extreme weather events.

“It’s a little bit concerning to see so many countries in Africa looking to build these massive new plants, when the economics of the electricity industry have for a long time moved towards less centralised power sources, which bring more resilience to power systems,” Mike Hogan, from the US think tank the Regulatory Assistance Project, told The Independent.

“These big signature infrastructure projects make people in power feel like they're doing something important, but it’s really a 20th Century solution to a 21st Century problem,” he added.

Russia, a country that has faced biting sanctions from the US and Europe over the illegal annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea in 2014 and the wider invasion in 2022, is seeking to expand its sphere of influence, so non-aligned nations in Africa that have long-struggled with underinvestment represent a logical focus for its nuclear industry. And the country’s partnerships have made nations take notice – with some 49 out of 54 African countries attending the last Russia–Africa economic summit in St Petersburg in 2023, despite heavy US pressure to stay away.

Many of the nuclear deals that have been signed by African nations are preliminary in nature, and only the very first step in the long and complex process of nuclear project development. But even these serve an important symbolic purpose for Russia in its current state of geopolitical isolation, believes Bellona’s Gorchakov.

Nuclear exports were worth around $16bn to Moscow in 2023 - far less than the $300bn value of Russia’s pre-war fossil fuel exports - but the sector is seen as a “prestige industry” to Moscow, Gorchakov says.

“For Moscow, the deals are not just about business: It is a tool of political influence,” he says.

This story is part of The Independent’s Rethinking Global Aid series

English (US) ·

English (US) ·