ARTICLE AD BOX

The Trump administration, in a matter of months, has tried to sweep away years of racial justice reform efforts that followed the brutal police killing of George Floyd in May 2020.

The Justice Department has dropped ongoing lawsuits against police agencies and pulled back on consent decrees between the government and troubled departments like Minneapolis, whose officers killed Floyd. Instead, the president has signed an executive order aimed at “unleashing” America’s police.

After the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, diversity, equity, and inclusion programs sprang up across government and industry alike, and Trump has committed to rapidly excising them from all parts of society.

His MAGA allies have even begun pushing for a pardon for Derek Chauvin, the white police officer who was convicted for his role in killing Floyd, a Black man who was arrested over using a counterfeit $20 bill and pleaded for minutes that he couldn’t breathe as officers knelt on his neck and back.

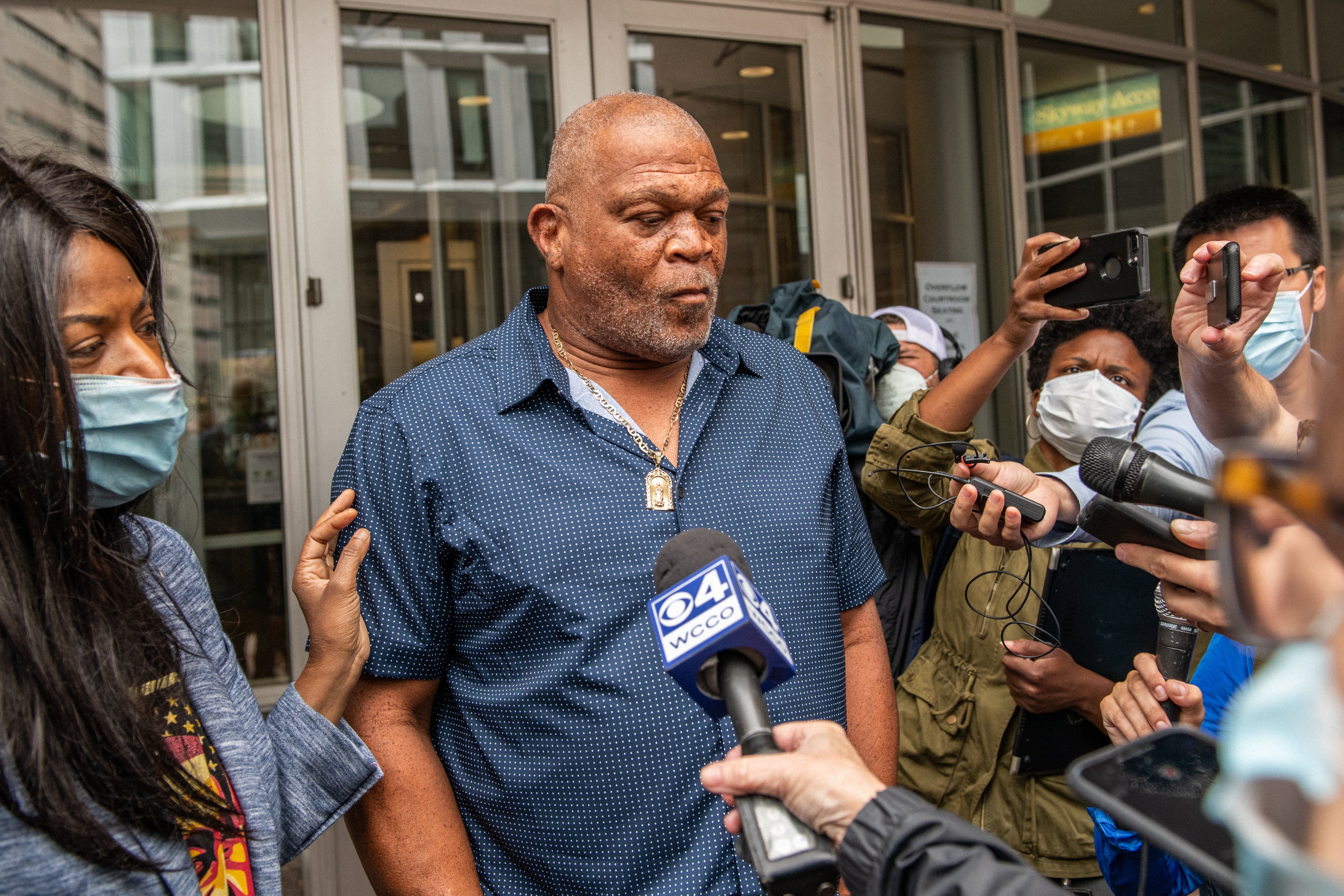

This change in momentum for the movement isn’t stopping Selwyn Jones, Floyd’s uncle, from continuing to push for police reform and racial justice, he told The Independent.

“It has faded, but we’re never going to let it pass,” he said.

“Everything slows down. It depends on the fighters you’ve got on the front line,” he continued, urging the kind of tenacity he once put to use as a professional indoor football player. “I’m a hell of a fighter…If you stop, you can’t win.”

Jones grew up in the Jim Crow South in a family of North Carolina sharecroppers, so he understands better than most how progress can move slowly. But in 2020, he said it began to ramp forward all at once.

“We’ve had more change in the last five years than we had in the last 60 years," he said.

Especially on the cultural front, according to the activist. There’s an openness about talking about race and policing that didn’t used to exist before his nephew was killed, the horrific video of his death spreading quickly online as millions of Americans were sequestered at home during the Covid pandemic.

“More people are coming out, stepping out,” Jones said. “People aren’t as afraid as they were once upon a time.”

On the legal front, cities, states, and, under the Biden administration, the federal government, moved to ban chokeholds and other violent tactics like the ones that killed Floyd.

Still, a push to pass a federal police reform bill, the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which would’ve ended some of the legal protections that often shield police from consequences in abuse cases, faltered under the past administration, while the flow of military-style weapons to departments never stopped.

Most tragically, data shows that the disproportionate police killing of people of color continued virtually unabated after 2020. In fact, 2024 was the worst year for such killings in at least a decade.

The odds may seem stacked against the movement now, but that hasn’t dimmed Jones’s fire. He’s still pushing for states to adopt provisions like the Medical Civil Rights Act, which grants an affirmative right for emergency medical care for people involved in interactions with police or jail personnel.

Such a right might have made a difference in Floyd’s arrest, where none of the four officers involved in restraining him attempted to give him CPR, even after he lost consciousness for minutes. So far, only Connecticut has adopted the bill.

Jones is also working on MYTH, a digital panic button app to record video and share alerts with family members in high-risk situations like an arrest or a missing persons case.

The activist considers himself non-partisan, more humanitarian than politician, but he’s also urging the administration not to pardon Chauvin.

“Pardoning Derek Chauvin in any way, shape, or form — not matter what he has to do or where has to go — is wrong,” Jones said. “You know that. I know that.”

Instead, Jones, CEO of the advocacy group 929 Justice, is hoping people can remember the humanity of families like his who have lost a loved one to violence. In his activism, traveling to rallies and conferences around the country, he’s been particularly struck by the mothers who have lost their children to police violence.

“The look in those ladies' eyes is something that you can’t even explain,” he said. “You can’t even imagine the hurt. I feel sad [about Floyd’s death] because I was his uncle and I loved him. Imagine if you nurtured and carried someone and fought for them.”

Looking back over the last five years, he also hopes people remember why they turned out to march in the first place.

The Black Lives Matter movement has been tarnished somewhat by financial scandals, including an Ohio man sentenced to prison on federal charges for raising over $450,000 for a dubious BLM charity, and a bitter legal battle over a legitimate foundation’s handling of the tens of millions of dollars in donations that flooded in after 2020.

“There’s a lot of people that fight for these family members and all they see is a dollar amount,” Jones said.

On May 25, Jones will be in Minneapolis, where the community plans to mark the occasion with marches, speeches, and a concert.

For Jones, the anniversary brings up a variety of mixed feelings. He served as a father figure to Floyd, and he remembers him as a “big a** comedian,” with Floyd quickly matching his uncle’s over six foot physique by the time he was a teenager.

“I miss his smile. I miss his laugh,” Jones said. Like Jones, Floyd grew up in poverty, in Houston rather than North Carolina, but “laughter was free, man,” Jones said.

No matter how far Jones has traveled, part of his mind always stays at the intersection of 38th Street and Chicago Avenue in Minneapolis, where Floyd was slowly killed in front of a crowd of local residents asking police to stop.

“That’s the last time my big baby took his last breath,” Jones said. “We have to fight for that man.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·