ARTICLE AD BOX

In A View to a Kill, Roger Moore’s final spin as James Bond, 007 surveys the corpse of a Parisian private eye, murdered at dinner with a poison-tipped fishing lure. Bond, pan deader than the victim, gravely observes: “There’s a fly in his soup.” Pause for applause, right? It’s pure, unadulterated, unapologetic Bond. Puns! Death! Fine tailoring! What more could you possibly want?

And yet, 40 years on from its release, A View to a Kill remains the worst-rated, and arguably most hated, official Bond film ever made, scoring a meagre 36 per cent on the reviews aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes. It’s also one of only two films in the 25-strong franchise ever to be nominated for a Razzie – the other, Die Another Day, is the second-worst-rated on Rotten Tomatoes, though it scored a considerably higher 56 per cent. And that has an invisible car in it.

Admittedly, Bond was in a weird place when A View to a Kill was released. It was Roger Moore’s seventh outing as the secret agent, Eon Productions was rapidly running out of Ian Fleming material to even loosely adapt, and the previous film, 1983’s Octopussy, had attracted mixed reviews. “The Bond wagon crawls along,” wrote Time magazine in its review of that movie. “Roger Moore is not getting any younger,” observed The New York Times.

Yet here we were, with yet another Moore-era Bond releasing into a summer already stuffed with exciting action properties, among them Back to the Future and sequels to Rambo, Rocky and Mad Max. How could Moore keep up? It was the film’s producers who allegedly convinced him to stay, rather than Moore pushing for the return himself. “I think, of all the Bonds that I did, I liked A View to a Kill the least,” he admitted on the commentary track for the film’s DVD release in 2005. “I think one of the reasons is that I was probably getting a bit tired.” Efforts were made to youth-ify the film elsewhere, but after the loss of both Priscilla Presley and David Bowie as potential co-stars, things looked rocky before the cameras even rolled.

But hindsight is a beautiful thing. Today, Bond’s future seems shakier than one of the spy’s signature martinis, with Amazon recently stirring things up, seizing the rights to the franchise and threatening world-dominating, spin-off-spawning action. So while many fans consider the series’ 14th entry its nadir, let’s all holster our Walthers for a second and stop taking potshots at what is actually an indispensable, delightful – and nostalgic – piece of Bond’s hallowed history.

Because that’s exactly what A View to a Kill is: the end of a golden era, and perhaps the last of the “fun” Bonds. Although they don’t play as well when viewed through the grittier, Daniel Craig-era lens, they remain a key part of the character’s DNA. This isn’t what we always want from Bond, but you can’t pick and choose from his history. Even Craig’s Bond has his quips; they’re just dialled up here. And the plot – of an industrialist hellbent on taking over the world by flooding Silicon Valley and controlling microchips – is vintage 007.

So let’s begin – as all Bonds do – with the gun barrel sequence, in which Moore is (naturally) wearing flares. When he turns his trousers on the audience, it may as well be a starting pistol he fires our way, because this film moves. First stop: Russia, where we see Bond on skis (something Craig didn’t manage in five overlong outings). From there to London, via the requisite slo-mo silhouettes and catchy theme song (which we’ll come back to). Then to Ascot, where there’s some equine doping afoot, and we get our first glimpse of the film’s villain (we’ll come back to him, too).

Fifteen minutes in, then, and we’re already in Paris, following Bond up his first big metal landmark of the film: the Eiffel Tower. His pursuit of a parachuting Grace Jones (playing the Amazonian henchwoman May Day, a blueprint for future Bond femmes fatales) is one of the best bits of A View to a Kill, with 007 commandeering a Renault 11 taxicab and throwing it up ramps and down steps – despite the car being sideswiped and literally sheared into an ever-smaller motor.

The chase culminates with 007 leaping from a bridge onto a party boat, where he plunges feet-first through a couple’s wedding cake (a neat visual analogy for this 007’s views on monogamy; the film sees him leap into bed with a franchise-high four different women.)

And yet, though it’s very clearly several stunt doubles taking Moore’s falls and crashes, the whole sequence shows a dedication to practical filmmaking that the modern, CG-reliant moviemaking machine appears to have all but abandoned. Perhaps only Tom Cruise’s Mission: Impossible franchise is risking it for real like this these days.

That’s not to say Moore was any Cruise, of course. But it does neatly steer us – in our ripped-apart Renault – to the main problem fans have with A View to a Kill: Moore’s advanced age. At 57, he was indeed too old. There’s no getting around that. Even Moore himself conceded that he “was only about 400 years too old for the part”. And yet, in the intervening years, ageing action heroes have caught on in a big way. Liam Neeson was 55 when Taken was released. Denzel Washington was almost 60 when he kicked off the Equalizer franchise. And former Bond Pierce Brosnan was similarly a sexagenarian when he appeared in The November Man.

While we’re on the Irishman, A View to a Kill seems to have been something of a blueprint for Brosnan’s own Bond adventures, with both featuring scientists who could be supermodels, henchwomen-turned-lovers, and businessmen baddies with airship lairs. The film even casts its shadow on Craig’s Bond era, as Christopher Walken was the first Academy Award winner to become a 007 villain. With Javier Bardem, Christoph Waltz and Rami Malek our three most recent megalomaniacs, an Oscar seems to have become a prerequisite for the part.

And Walken! Oh, Walken! The part of Max Zorin – nefarious industrialist, Nazi experiment and stone-cold psychopath – was the role originally offered to Bowie, but we’re eternally glad it went to Walken. Because he killed it. Actually, he killed everything and everyone in sight (Zorin is arguably the most murderous Bond villain of the entire franchise). He tosses a molotov cocktail down a lift shaft! His airship has a slide down which he sends his detractors! He even machine-guns scores of his own workers while they’re frying in an electrified underground lake, which is also in a collapsing mine. How could such high stakes yield such low ratings?

Today, too, Walken’s villain echoes particularly loudly. An overseas tech tycoon bent on controlling the world from Silicon Valley? Sound familiar? Throw in his bleach-blond coif, unpredictable speech pattern and love of bright red ties, and it’s almost prophetic. In fact, there are many such cases of A View to a Kill predicting and inspiring the future. A sequence in Zorin’s office was the catalyst for the CIA to develop real-life facial recognition software. Official snowboarding bodies credit the film with bringing the sport to prominence, especially among Brits. And, as mentioned, in blending beauty with brawn, Jones’s May Day laid the groundwork for female characters from Famke Janssen’s Xenia Onatopp in GoldenEye to Lashana Lynch’s Nomi in No Time to Die.

The Bond films had come up short in the past when it comes to strong female representation, but Jones changed that, and makes an excellent case for being the most important action character of the entire Eighties. (Even stronger than the burly Dolph Lundgren, Jones’s then boyfriend who – mere months before Rocky IV – made his film debut in A View to a Kill as a KGB bodyguard.)

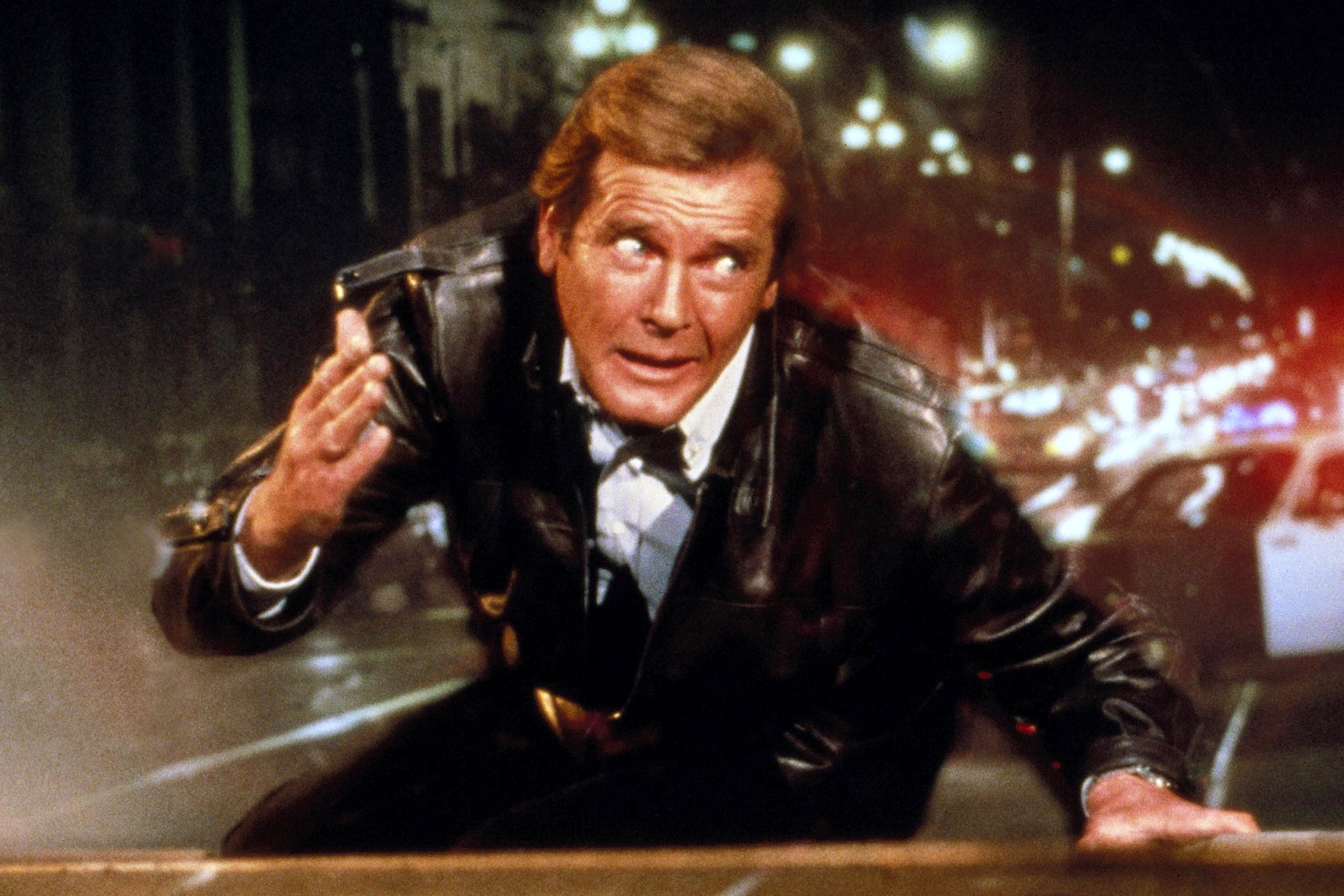

So that’s stunts, villains, and a little light prognostication. What else does A View to a Kill have going for it? Bond himself, of course. Despite his age, Moore is in full martial-arts swing for this one, karate chopping and dispatching villains everywhere from Siberia to San Francisco. He does a somersault with a shotgun at one point, and takes down a helicopter with a flare gun before the titles even roll. He jumps a moat! He says “Bond. James Bond” twice in the space of a minute! The brakes are off! And Bond puts his own spin on the iconic San Francisco car chase trope by hijacking a fire engine (a scene in which Moore, who drove lorries in the army before becoming an actor, even did some of his own stunt driving). Eat your heart out, Steve McQueen.

But one of the very few strikes against A View to a Kill is also automotive. During his previous MI6 missions, Moore had collected the keys to two handsome Lotus Esprits – but he forgot to squeeze a signature motor into his swan song (we don’t count the Renault). Fiona Fullerton’s Soviet spy Pola Ivanova gets a decent Chevrolet Corvette, and Patrick Macnee briefly turns up in a Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud, but there’s nothing to get the petrolheads really panting. In fact, Bond’s kit is lacking a little across the board, with another strike being the distinct dearth of Q-branch gadgets.

A franchise fundamental that does deliver? The theme song. Duran Duran’s eponymous chart-topper was a bona fide hit. It remains the only Bond theme to reach No 1 on the US Billboard Hot 100, and was the highest-charting Bond theme in Britain until Adele’s “Skyfall”. It’s a guns-blazing, 60-piece-orchestrated ode to all that makes Bond themes great – and was co-written by John Barry. Rolling Stone magazine may only have ranked it as the 12th-best Bond theme, but Classic FM (arbiters of taste, clearly) put it in the top 10, where it belongs.

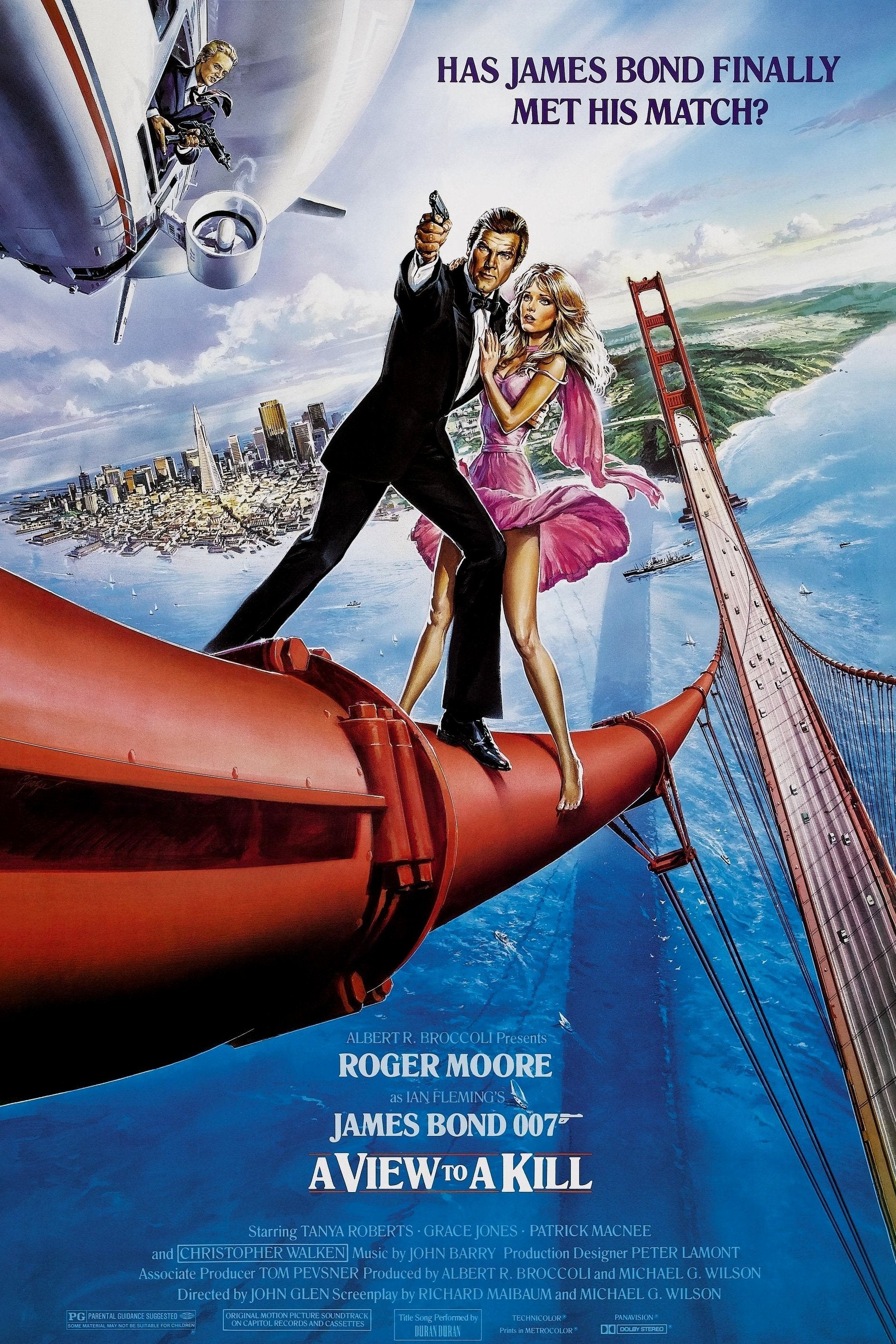

Anything else? The poster, probably, remains the last decent 007 one-sheet. You know the one: Bond perched on the Golden Gate Bridge (there’s that second big metal landmark), with Tanya Roberts’s age-inappropriate Bond girl (Moore was older than her mother) in one hand and his Walther in the other. It’s an enduring image, and one that neatly illustrates why this brilliantly bombastic Bond is one of the best, not the worst.

Yes, A View to a Kill is packed with campy clichés and questionable cuts, but it isn’t ashamed of being a reliable, by-numbers Bond film – something subsequent offerings, such as the risible Quantum of Solace, seemed to struggle with. And with the future of the franchise so uncertain, a film that sticks to the recipe feels like a lifeline we should be grabbing on to and celebrating. So yes, Moore could have done with a decent car, a pocketful of gadgets, and possibly a facelift, but – even if you’re still not swayed – what’s one show-jumping, shark-jumping victory lap when he’d given so much to the series already?

English (US) ·

English (US) ·