ARTICLE AD BOX

In his 1998 novel The Hours, writer Michael Cunningham imagines Virginia Woolf sitting down to do battle with the draft of a book that will eventually become Mrs Dalloway. “Can a single day in the life of an ordinary woman be made into enough for a novel?” his fictional version of the novelist ponders.

The sweet, sad irony, of course, is that any reader of Mrs Dalloway knows that she needn’t fret: the answer to Woolf’s self-questioning is a resounding “yes”. She is, in fact, working on a story so dazzling and expansive that it will prove irresistible to generations of readers to come, including writers like Cunningham. A century on from its debut, Woolf’s fourth novel is “as vital as ever”, says Vintage Classics editor Charlotte Knight. To read it 100 years later is to be shocked by its immediacy and the sheer audacity of its experimentation; it’s no wonder that contemporary authors are still in its thrall.

Released on 14 May 1925, Mrs Dalloway was published by the Hogarth Press, the publishing house run by Woolf and her husband, Leonard. Production was a family affair. The cover – a simple but expressive yellow and black ink painting of a bouquet left on a windowsill – was illustrated by her older sister, the Bloomsbury Group painter Vanessa Bell. It now appears on Vintage’s new centenary edition, taking us back to a time when the Woolfs were “collaborating with friends and family”, Knight says. “Two sisters, the artist and the writer, came together to produce something that defined a moment but that still feels fresh and free 100 years later.”

A year before Mrs Dalloway’s release, Woolf had set out a manifesto for a new approach to fiction in an essay titled “Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown”. While older, more traditional novelists had always created characters by summoning various external details – their salaries, their homes, the way they look and dress – Woolf instead made the case for looking inward, attempting to capture how a person’s mind might dance from thought to impression to memory and back.

She’d already experimented with an impressionistic, stream of consciousness style in Jacob’s Room, her third book, but in Mrs Dalloway she fine-tuned this quest to capture a person’s inner life – and it would prove to be her breakout success. “It had a first print run of just 2,000 copies, but it was critically well-received, and before long the book was reprinted and reprinted again. And it has never been out of print since,” says Knight.

Reduced to its component parts, Mrs Dalloway is indeed the story of “a single day in the life of an ordinary woman”. Woolf makes her protagonist ordinary in the sense that she is not an especially brilliant, beautiful, heroic or notable person, beyond her socioeconomic circumstance (she lives in Westminster as the wealthy wife of a Tory MP). In the middle of a bright June morning, 52-year-old Clarissa Dalloway leaves her house in the midst of preparations for the party she is hosting later that evening.

Her intention is to pick up some bouquets for later – to “buy the flowers herself”, as the novel’s opening line puts it – and relieve her servant, Lucy, from one task on a long to-do list. But Clarissa’s journey through London will also prompt a reflection on her younger years as she reckons with all the parallel lives she could have lived: the man she might have married, the girl she once kissed. Those memories are just as vivid as the sights and sounds she encounters on her walk; they are not deeply buried but instead jostle around at the top of her consciousness, waiting to bloom again.

As she travels across the city, another character is making his own parallel journey. Septimus Warren Smith is a soldier suffering from shell shock after fighting in the trenches of the First World War. For him, London’s stimuli are overwhelming and often frightening, on the verge of exploding into some fresh horror; the city “waver[s] and quiver[s] and threaten[s] to burst into flames”. He is, in a sense, Clarissa’s double, her shadow self, acting out some of her more confused, darker impulses.

Clarissa’s journey through London will also prompt a reflection on her younger years as she reckons with all the parallel lives she could have lived

And he is Woolf’s double, too. Writing his unravelling, the author drew from hallucinations she’d experienced during her own periods of mental breakdown – a vision of birds singing in Greek, for example. Perhaps that is why painful emotions feel so close to the surface throughout the novel despite the flowers and the dresses. And certainly, despite Woolf’s misplaced fear that, in Clarissa, she’d written an overly “tinselly” character.

Clare Hutton is professor of literature and book history at Loughborough University, where, like thousands of academics across the world, she teaches Mrs Dalloway to a new cohort of students every year. When those students come to the novel, she says, often “they think Virginia Woolf is a snob, and that she was antisemitic, and both of those things are true”. (Woolf’s diaries and letters included racist remarks and stereotypes). Yet, she says, they are then also struck by the book’s “palpable” depiction of vulnerability. “Clarissa Dalloway’s vulnerability is explored so exactly… those subtle shifts in her mind and feelings as she goes through the day,” says Hutton.

On the face of it, Hutton adds, “the day should be easy and pleasant, and her life should be easy and pleasant”, but this is far from the case. “We live in an age of mental health crisis and interiority, where people are exploring fragility,” she says, “and so [readers] suddenly see this book that’s 100 years old, and they think it won’t necessarily speak to them – and then they find it does.”

Woolf’s writing has a fluid quality that ensures a different reading experience each time you return to it. Certain lines or scenes, ones that might previously have slipped away from you as you’re propelled forward by those long, stream-of-consciousness sentences, seem to suddenly expand or burst into light. “There is something new in it with every reading, and not just in the story but in every soaring, intricate sentence,” suggests Vintage Classics editor Knight.

When I first embarked on the book as a self-serious teenager, it was the vitality of the London summer day, and the constant, dizzying momentum of her prose that stayed with me. Returning to it about a decade and a half later, in my early thirties, I’m struck instead by the sense of might-have-beens that haunt the story, and how contingent and fragile everything seems beneath the city’s sun-soaked surface. “She always had the feeling that it was very, very dangerous to live even one day,” Woolf writes of Clarissa, making the ordinary seem both appealing and unsettling, a source of wonder and horror.

It’s the day-in-the-life concept that has authors returning to Mrs Dalloway as a point of inspiration, reckons Reverend Jane de Gay, professor in English Literature at Leeds Trinity University and renowned Woolf expert. “It’s the structure of the day, and the power of the memories that interface within that day,” she says. “I think it’s inspired people to explore the ways in which our present is so much influenced by our past.”

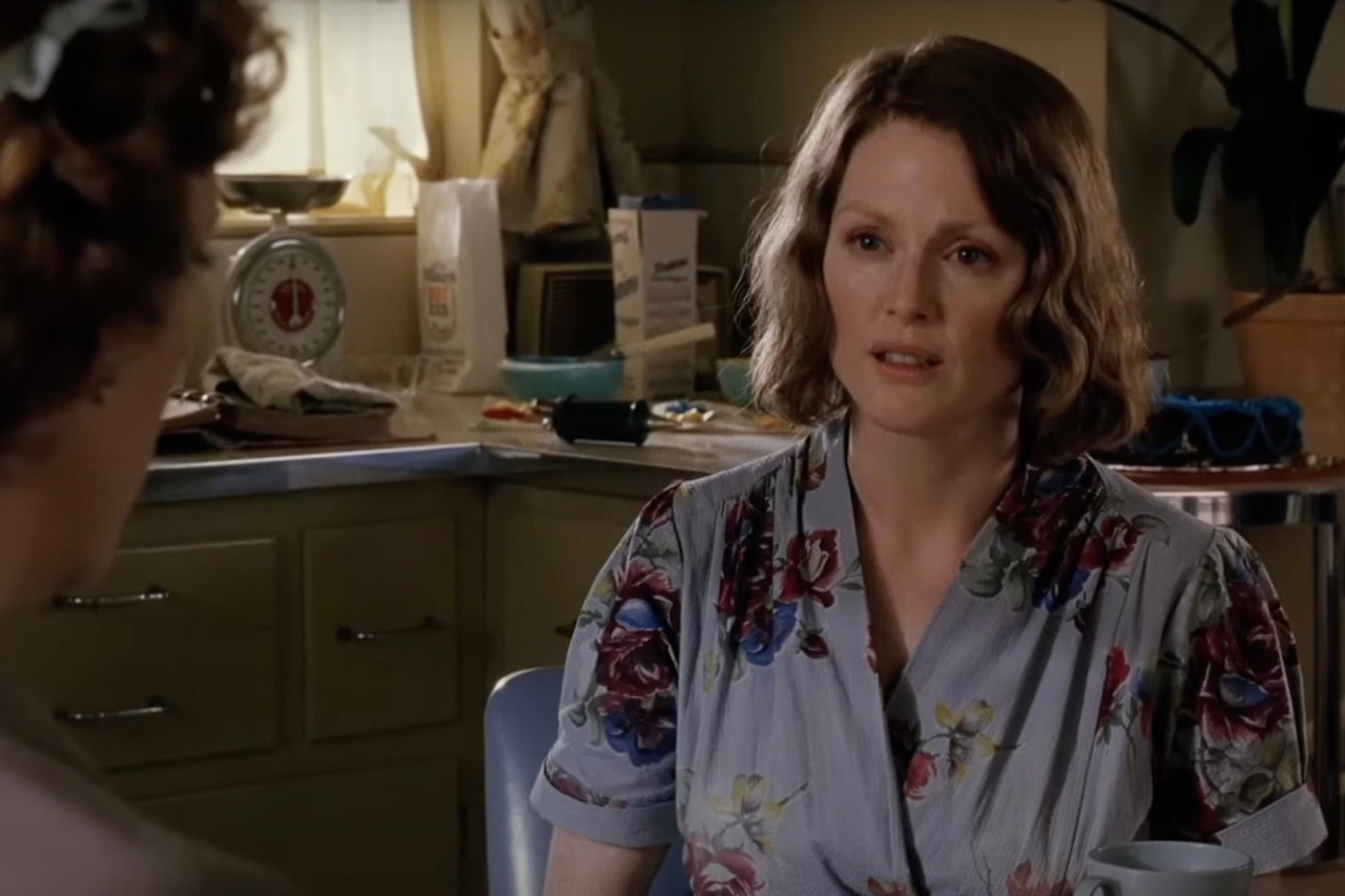

In The Hours, named after Woolf’s working title for Mrs Dalloway, Cunningham borrows this framework to tell the stories of three women, and to echo some of the near-universal experiences – dissatisfaction, mortality, madness – explored in the original novel. There’s the author, working on her book in 1923. There’s Laura Brown, a Forties housewife in Los Angeles reading Mrs Dalloway for the first time and feeling hollowed out by her domestic obligations. (“Mrs Brown” is surely a nod to Woolf’s 1924 essay.) And in the novel’s present day, there is Clarissa Vaughan, preparing for a party she’s throwing for Richard, a celebrated poet and her former lover, who is dying of an Aids-related illness.

She took her chances during periods of good health to write in an extraordinarily ambitious and original way

Charlotte Knight, Vintage Books

These characters may not cross paths straightforwardly, but their similarities reverberate across the three timelines in striking and Woolf-like ways. Richard is the novel’s Septimus. Cunningham, de Gay says, “takes one tragedy from the beginning of the century” – shell shock and its stigmatisation – and draws a line to another “tragedy going on at the end of the century”, the Aids epidemic.

Cunningham’s novel, and its 2002 film adaptation starring the Hollywood trinity of Nicole Kidman, Julianne Moore and Meryl Streep, may be the most direct reimagining of Mrs Dalloway, but its legacy extends much further. You can hear very obvious echoes of her novel in the slew of contemporary fiction that examines interiority in minute detail, often while the protagonist traverses a city. Ian McEwan’s 2005 book Saturday borrows the day-in-the-life structure as he follows a neurosurgeon around London on the eve of an Iraq War protest. Zadie Smith’s 2012 book NW, with its quartet of interconnected characters pacing very different routes across London, plays with a handful of scenes from Woolf’s original.

And more recently, Natasha Brown’s debut Assembly, which follows a young Black woman as she prepares to attend a garden party at a country house owned by her white boyfriend’s wealthy parents, was hailed as “a modern Mrs Dalloway” upon its release in 2021. It’s not just the novel’s set-up that feels Dalloway-esque, but the fluidity of Brown’s writing, and the specificity with which she paints her protagonist’s alienation.

There is also, inevitably, a “voyeuristic” appeal to Woolf’s work, and to Mrs Dalloway in particular, de Gay adds, because of the parallels with her own mental health struggles, and her eventual suicide in 1941. The Hours, of course, famously opens with the moment of her death. But it’s a mistake, I think, to define her and her book in this way.

The older I get, the more poignant and even defiant Woolf’s insistence on writing in the face of her illness seems. As Knight puts it, “she had terrible struggles with depression, which marred her life and interrupted her writing, and yet she took her chances during periods of good health to write in an extraordinarily ambitious and original way”. Mrs Dalloway is a novel shadowed by death but, somehow, that doesn’t darken the wonderful bright spots or dampen its vitality. Every time that we return to it, we feel, as Woolf writes, that “somehow in the streets of London, on the ebb and flow of things, here, there, she survived”.

Vintage Classics' centenary edition of ‘Mrs Dalloway’ is available now, £20

English (US) ·

English (US) ·