ARTICLE AD BOX

I’d like to know where all the strange ones go,” belted out Gaz Coombes on track one side one of Supergrass’s 1995 debut album. In real life, they were all around him. There was Cosmic Bob, ragged denizen of Oxford’s Market Street cafes, with his notebooks full of diagrams proving that humans were secretly alien life forms. Chris and Julie, the travellers camped up at nearby Shotover country park who’d take the band “driving around in cars and f***ing things up” every afternoon for weeks, until they’d played truant enough to get expelled from school. Daryl the band’s ex-army housemate who’d poke his head out of the shower to make lyrical suggestions during writing sessions. Caught by the fuzz, you say? “I was still on a buzz!” a damp-haired Daryl exclaimed.

These were the local outcasts and oddballs who inspired and populated I Should Coco, colourful extras in the background cast of Nineties British pop culture alongside Tracy Jacks (from Blur’s Parklife), Pulp’s Grecian poverty tourist (from “Common People”) and Elsa the Alka-Seltzer addicted dog (from Oasis’s “Supersonic”). But the album track that immortalised them – “Strange Ones” – was as much Supergrass self-portrait as weirdo-based city guide. “We were little hippies, little f***ing street urchins,” says drummer Danny Goffey, joining his bandmates on Zoom from a stately, mirror-festooned lounge. “We didn’t want to walk around town wearing Nike track suits. We’d probably rather wear some strange velour, slightly wizardy outfit because it was just fun to dress up weirdly.”

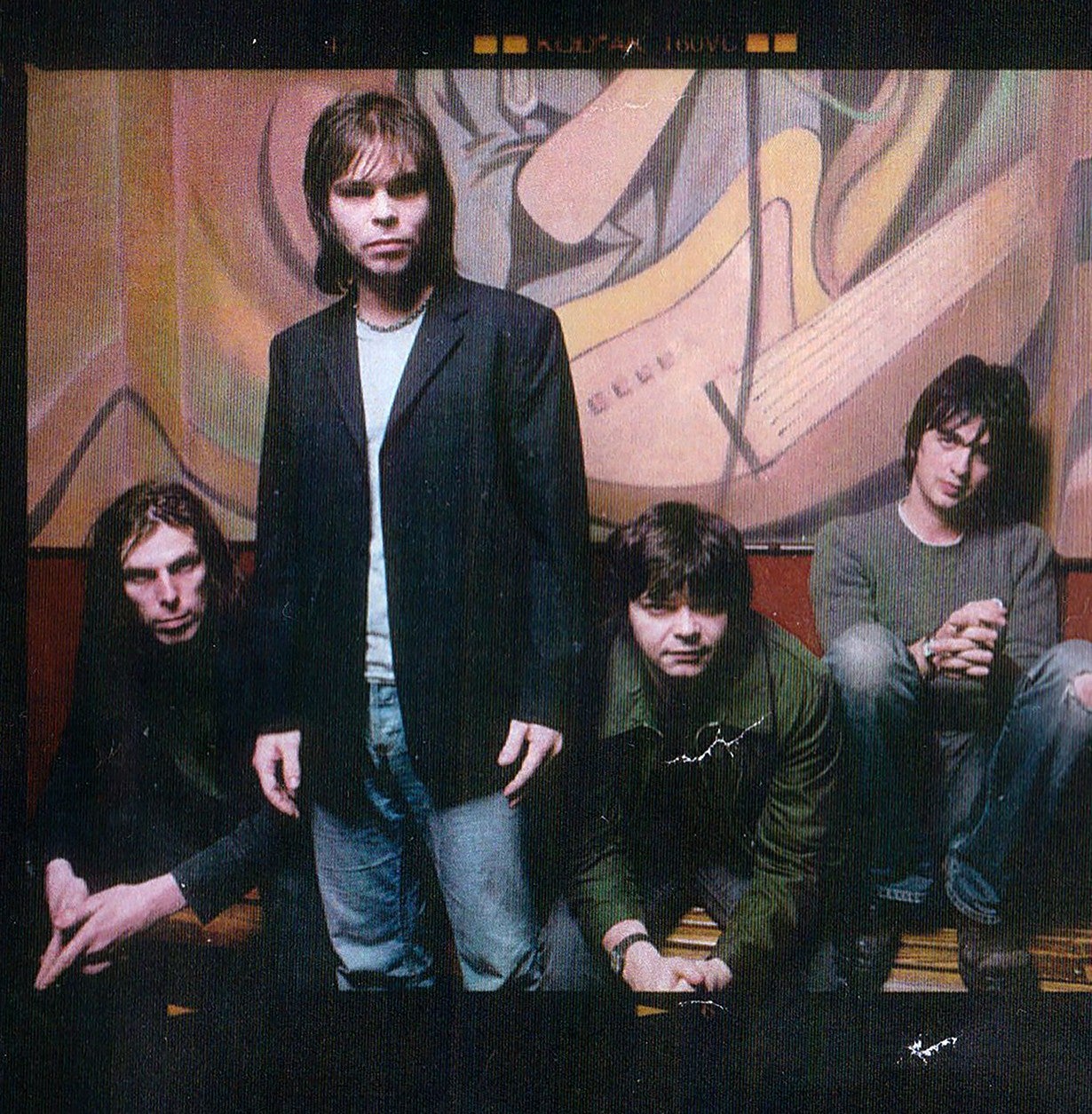

The lunatics, it’s fair to say, swiftly stormed the asylum. On its release 30 years ago this week, I Should Coco topped the UK charts, sold a million and made instant stars of its trio of monkeyish miscreants. To mark the anniversary of one of rock’s most rabid and mutton-chopped breakthroughs, the Oxford band – now a quartet of Goffey, singer Gaz Coombes, his keyboardist brother Rob and bassist Mick Quinn – are currently touring the album in full, and with fresh perspective.

Once, we might have reduced the album to merely one of the definitive peak Britpop releases. Famed for era-defining hits such as “Caught by the Fuzz” and “Alright”, and its breathless punk-pop paeans to minor drug busts, misfit gangs and dentally impeccable hi-jinks, it dovetailed with the movement’s overground push, swiftly considered the trouble-prone younger sibling of Pulp’s Different Class, Oasis’s Definitely Maybe and Blur’s Parklife. Three decades on, though, the record has transcended all limitations of trend and scene.

More than any other album of its time, I Should Coco now epitomises the exuberance of Britain’s musical attitude in the Nineties and stands as one of rock’s most enduring, no-filter documents of the teenage experience. “I’ve got a 16-year-old daughter and her and her mates, they all know the I Should Coco album,” says Coombes from a smart home studio. “It’s one of those records that, when you get the first vinyl player, it’s in there with a pretty illustrious bunch of other cool records that the teenagers seem to gravitate towards.”

And even deep into middle age (Coombes is now 49, Quinn the Supergrass elder at 55), the band themselves can still connect to a record they made as relative tykes. “Some of them, you wrote those in your twenties, there’s some really obvious chord changes in it, it’s difficult to relate to some of the subject matter,” says Quinn, “but there’s a few songs on there that you can get your teeth into.” Coombes, too, feels I Should Coco’s tracks still stand up. “I don’t think we’d be playing them so happily and comfortably if they didn’t have this timeless quality to them. We did a warm up gig at the start of April, and it was great just to snap into those moments and all those time changes and the chemistry that we have together. It’s nice to visit nostalgia – not for very long, but just pass by.”

Over a jocular hour, we make just such a (figurative) drive-by. Past the row of cottages in the village of Wheatley outside Oxford where, around 1993, Supergrass rose from the ashes of Coombes and Goffey’s “Sixties hippie” school band The Jennifers. Pumped up on Madchester, early Who, Gong and The Muppets, the band would jam out their pent-up energy in Quinn’s parents’ living room every chance they got, surrounded by a gaggle of curious local characters – soldiers, doctors, the village dope dealer who lived next door. “It was a really mad, diverse bunch of people,” Coombes grins, “we were kind of in our own bubble.”

It was here – after the teenage weed arrest and traumatic police interrogation that inspired their supersonic debut single “Caught by the Fuzz” – that Coombes’s mum made what he now calls “an intervention” to discuss his blackening of the family name. “I remember we were all sat around the kitchen table, and it was this big serious thing,” says Rob. “But it didn’t really work, because we were all going, ‘yeah, so?’.” Coombes remains unbothered about releasing his childhood charge sheet to the world: “It could have been anything, it could’ve been shoplifting.” “I still shoplift quite a lot,” Goffey jokes in solidarity. “Only from huge establishments, not the small men.”

We glide down Cowley Road, where the growing ’Grass and their coterie of like-minded creatives briefly lived on social security and housing benefit as their songs cohered. “You had enough time to spend on making music and enough money to buy beer with, basically, and that was it,” Goffey says. “Maybe a bit of dealing on the side, here and there.” And past local pubs like The Bullingdon, the Elm Tree and the King and Queen, which they filled with moshing mates for early gigs and where they were spotted by producer Sam Williams, who invited them to record six songs in his Sawmills studio in Cornwall.

Drumming songs like “Strange Ones” and “I’d Like to Know” today (the second inspired by playing a tape of the first backwards), Goffey feels the strain of their velocity. “The first eight or nine songs are about 150 miles an hour,” he says, “the faster the better in those days.” Quinn puts their turbocharged urgency down to youthful hormones and garrotte-tight budgets. “I think we had to bang them all out in about five days,” he says. “That was also essentially our live set. That’s how we played in the pubs. We were playing at that kind of speed.”

These were vibrant, primary coloured punk pop songs more closely aligned to the Buzzcocks or “new wave of new wave” bands like S*M*A*S*H and These Animal Men than the arch and/or surly Britpop of Blur, Pulp and Oasis. But independent, 500-copy vinyl releases of “Caught by the Fuzz” and “Mansize Rooster” in 1994 started filling their pub gigs with local scenesters and, signing to Parlophone, Supergrass became larrikin heroes of the music press overnight. By the end of the year they’d invaded the charts with the major label re-releases of both singles and landed in the top end of John Peel’s Festive Fifty. “I remember sitting in the bath and listening to it as a 19-year-old and it getting lower and lower,” Goffey says. “It got into the top 10 and we weren’t in it. I was really disappointed. Then they got to number five, and ‘Caught by the Fuzz’ was number five. It was the best thing that had ever happened to us.”

Live, the lift-off point was on tour supporting Shed Seven in Dundee. The instant Supergrass started their set, pandemonium almost ended it. “About 10 bare-chested blokes threw all their beer all over Rob’s keyboard and piled in, and things got smashed,” says Goffey. Coombes had to catch the PA as it toppled on his head and their lager-drenched equipment started playing its own Skrillex gig. Amid the chaos, Goffey’s eyes were opened. “That was the point where we realised, f***ing hell, people are really into this.”

About 10 bare-chested blokes threw all their beer all over Rob’s keyboard and piled in, and things got smashed

Danny Goffey

A relatively gargantuan Parlophone recording budget allowed the band to stretch out on a second studio session, indulging more retro psych and classic rock influences on “Time” and six-minute astral voyage “Sofa (of My Lethargy)”. “The further we got into the studio stash of weed, the more psychedelic we went,” Coombes says. But it was a more timely and cocktail-friendly tune which came to define the record.

The band’s relationship with their first Number Two smash “Alright” – a celebratory catalogue of teenage larks set to a none-more-jaunty hula groove – is, Quinn admits, “complicated”. Goffey is proud that its “memorable” (nay, iconic) bed-riding video was self-made among their team of close friends rather than the result of label image manipulation, but he finds it something of a “cringy” misrepresentation of the band that shackled them to the era. “It was quite a cartoony, jolly video and it ticked the Britpop boxes,” he says. And they’re sanguine about lyrics they threw at the page 30 years ago, casually rhyming “we are young, we run green” with “keep our teeth nice and clean” and detailing Goffey’s joyriding antics across local fields in his parent’s clapped-out car. “You would never, ever think ‘f***ing hell, I’m going to be singing this in 30 years’ time’,” Goffey chuckles.

Coombes, however, remains proud of the song’s subtle quirks. “I always get quite a lot of pleasure from the fact that it’s a bit of an odd song still,” he says. “The chorus is a bit odd. It’s not a big chorus for such a hit… It’s like having your cake and eating it a little bit.” He’s still amazed that he was able to write a song with such a tearaway life of its own. “You get these songs through any decade that people are still playing 30, 40 years later, and every summer it comes out, or it just ends up on some advert here or there. We gave in to it a long time ago.”

Britpop, to Supergrass, was a happy by-product of vibrant musical times. “It was just a neat and tidy way of packaging all the good, energetic, youthful music of that period,” Coombes argues, “We didn’t really court it or snub it, we just did our thing.” But by bypassing the social despond that lurked behind the scene’s suburban pop sparkle, “Alright” came to define the era – all harm-free hooliganism and uncynical teenage kicks. And it soon saw them on a plane to America for a meeting with Steven Spielberg about becoming a real-life cartoon.

“It was like a weird acid trip,” Goffey recalls, “we’d grown up watching ET and that stuff.” “It was an amazing experience to meet him,” Coombes adds. “I remember sitting next to him in a meeting and talking about old Twilight Zone episodes.” A Monkees-style TV series was proposed, featuring the band all living together and going on weekly rock-based adventures. “We all just looked at each other after the event and were like ‘we need to make album number two’, and then sort of laughed about the experience and that was that,” says Coombes. “I don’t know how long it would have lasted if we’d have taken that turn.”

.jpg)

Instead, fame played gently with the ‘Grass. I Should Coco formed the foundation of a three-decade career that’s still on a buzz, peppered with more mature but no less classic albums: 1997’s In It for the Money, 1999’s Supergrass and 2005’s Road to Rouen amongst the highlights. “Back then, it’s different times,” says Coombes. “It wasn’t immediate. I don’t know how people can handle just going viral now, millions of people seeing their faces overnight. I don’t know what that does to your mental wellbeing.”

As they limber up those speed-drumming muscles, polish their pearlies and shiver once more at the memory of a copper’s hand on their shoulder, what would they say to the kids who made I Should Coco? “They probably know more than we do now, in a way,” muses Quinn. “The innocence on the record is brilliant. There are seeds on that record for everywhere we went afterwards. So I don’t think we’d tell them anything, and you wouldn’t be able to. They wouldn’t take you seriously.”

See Supergrass celebrate 30 years of ‘I Should Coco’ at Wilderness Festival on Saturday 2 August, tickets on sale now

English (US) ·

English (US) ·